Energy transition minerals in Ghana

A critical time for Ghana's mining sector

As countries take steps towards a net-zero future, striking a balance between energy security, equitable economic growth and environmental sustainability will be key. The time is ripe for Ghana to leverage opportunities and address risks associated with its critical minerals.

In some African countries with significant fossil fuels, public policy discussions around the energy transition have centred around perceived risks associated with the transition – undeveloped oil fields, stranded assets and untapped oil revenues. Though Africa is estimated to account for 3% of global energy-related CO2 emissions, more than half of African oil production is projected to be rendered commercially unviable by 2040. To respond to such concerns, Ghana set up the National Energy Transition Committee (NETC) in December 2021 to develop its energy transition policy.

A recent study, commissioned by Ghana’s EITI multi-stakeholder group (GHEITI), examines the status of Ghana’s critical minerals sector and associated governance risks and opportunities.

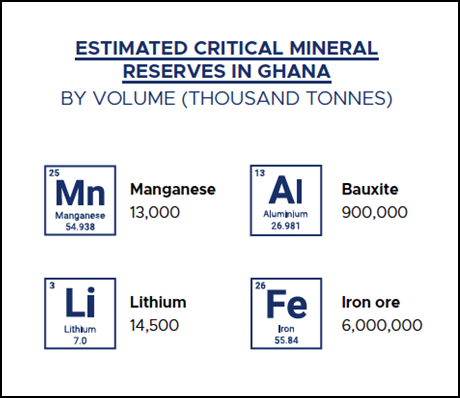

The study documents Ghana’s proven reserves of at least four critical minerals, which are expected to see an increase in demand as the move to meet net-zero goals ushers in new energy technologies, many of which rely on these minerals.

Ghana’s history of mineral production: What does the data show?

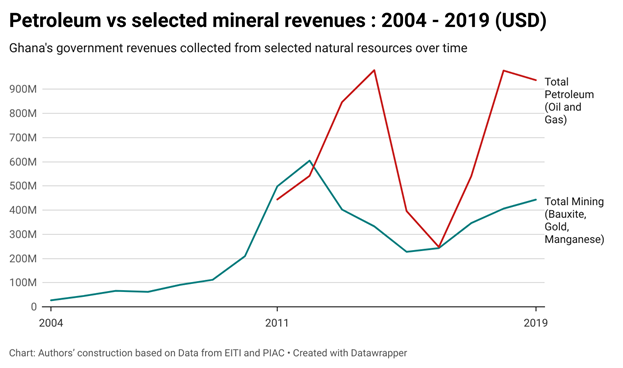

A multi-year review (2004-2019) of trends in mineral production shows limited government revenue generated from mining despite significant production volumes. For example, GHEITI’s reporting estimated exports of bauxite at 1.1 million metric tonnes in 2019, generating about USD 35.2 million in export value. The country, however, only received USD 1.47 million in net revenues, equivalent to 4.17% value retention per exported tonne. In contrast, Ghana’s upstream oil and gas sector, which has only been commercially exporting hydrocarbons since 2011, has generated more revenues (approximately USD 6 billion) than bauxite, gold and manganese revenues combined (USD 4.1 billion).

Leveraging opportunities

Ghana’s mining legal regime is generally regarded as adequate in regulating the sector. Yet the limited revenues earned from mining over the past decades suggest the need to optimise the mining legal and fiscal regime to respond to global demand for critical minerals and capture more value beyond solely extracting for export. To do so, there is the need to update mining laws, policies and practices and align them both economically (with well-defined industrial development strategy) and ecologically (with commitments to meeting climate targets). The ongoing review of the Minerals and Mines Act offers an opportunity.

According to the GHEITI study, which uses conservative price estimates, Ghana could have generated an estimated USD 330 million by deciding to refine its bauxite into alumina (the starting material for the smelting of aluminum metal). A critical minerals strategy and action plan – anchored on providing relatively cheaper and reliable electricity (especially for aluminium refining and smelting), developing rail, road and port infrastructure to transport products, and addressing the adverse environmental effects of mineral production – would be a tactical step in defining a pathway to optimise value creation in the critical minerals boom.

Managing risks

Several risks may heighten across the extractive value chain, given the projected hike in demand for critical minerals. At the early stages of the value chain, the award of mining rights and contracts could become vulnerable. As some studies have shown, Ghana and other developing countries typically enter into contractual negotiations with a comparatively weaker hand, in part due to the lack of accurate data on the types, quality and commerciality of mineral resources. This is equally an issue for critical minerals, exacerbated by the pace at which new projects are emerging.

To address these risks, transparent and accountable governance systems need to be strengthened before new licenses for critical minerals are awarded. This will require, for example, open due diligence processes to check corporate ownership chains and other Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) indicators prior to awarding mining rights. Together with transparent processes, adequately funded government agencies can play a key role in improving access to data and government’s bargaining power as it enters into negotiations on new contracts.

While Ghana has taken commendable steps to disclose corporate ownership information, mining licenses and contracts, sustained systematic disclosure of approved contracts and the real beneficial owners of mining companies would allow citizens to know who they are doing business with, whether a fair deal has been achieved and whether companies are meeting contractual obligations. There is also the need to strengthen corporate governance of the two newly-established state-owned enterprises in the mining sector – GIISDEC and GIADEC – and to ensure that revenues from the anticipated boom are collected and managed to the benefit of Ghanaians.

A broad strategy is needed

Ghana’s nationwide consultation to develop a national energy transition policy is a positive step. Yet, the resulting policy will be insufficient without considering the opportunities and risks associated with critical minerals. To this end, policymakers could draw on GHEITI’s annual disclosures, which offer an annual diagnostic on the state of license allocations, contract disclosure, state participation, social and environmental expenditures, among other areas. GHEITI also offers a multi-stakeholder platform to engage technical expertise from government, civil society and industry on the prudent management of these minerals. GHEITI is already embarking on a new project with local community stakeholders in the Ellembelle District to raise awareness and amplify their voices on energy and extractives governance in a just transition.

As governments continue to seek pathways to a sustainable future, a balance between energy, economic development and environment is crucial. For Ghana, the time may be ripe to realise the potential of the mining sector in the pursuit of global sustainability goals.

Related content