Malawi's journey to full contract transparency

Malawi's journey to full contract transparency

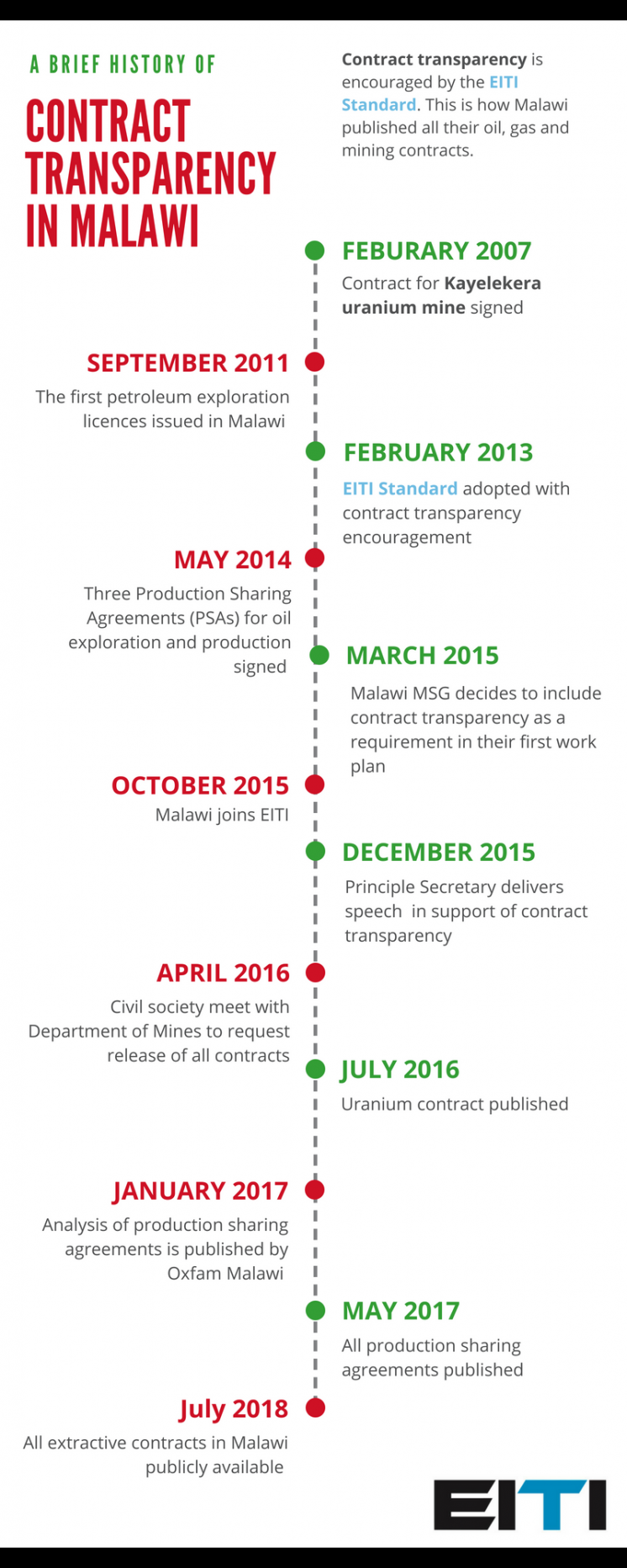

The Government of Malawi formally committed to disclose all oil, gas and mining contracts in December 2015 at a Malawi EITI stakeholders meeting in Lilongwe. At the meeting, the then Principal Secretary Ben Botolo responsible for mining said that all contracts were already available upon request at the Department of Mines. As civil society, we were quick to take government at their word. But we soon discovered that while mining contracts were easily accessible, petroleum production sharing agreements (PSAs) that had been signed just days before the 2014 elections were still not readily available.

Using EITI to make contracts public

Malawi’s largest mining project to date is Kayelekera Uranium Mine, though the mine has been on care and maintenance for the last four years following the fall in uranium prices and ongoing high operating costs. The mining development agreement the government signed with Dutch and Malawian subsidiaries of Paladin Energy in 2007 for the project was not public. Civil society and members of parliament repeatedly asked for the agreement to be made public, but the government said it was restricted by a confidentiality clause. However, there is in fact no confidentiality provision in the contract so staff at the mining company indicated their willingness to share the agreement. Paladin Energy, listed in Australia and Canada, had already made the fiscal terms public to its shareholders in 2007.

In 2015, almost ten years after this agreement was signed, as Malawi started preparing its EITI application, the multi-stakeholder group unanimously decided to include contract transparency in the first work plan. Contract disclosure is recommended in section 2.4 of the EITI Standard. Several civil servants that were part of the group demanded greater contract transparency. They had not seen some of the signed agreements between the government and companies, despite their important role in revenue management and tax administration of the sector.

To encourage the release of the contracts, civil society from the multi-stakeholder group, who were also part of the Natural Resources Justice Network and Publish What You Pay Malawi networks, got to work. We met with the Director of Mines Charles Kaphwiyo, submitted a letter to the Principal Secretary Patrick Matanda and copied in the Malawi EITI Secretariat to enable the Secretariat to help make the goal a reality. At each multi-stakeholder group meeting, a civil society representative would follow up on the issue of official disclosure.

The beginning of contract disclosure

Progress on contract transparency only came after the government became an EITI member. The Department of Mines was able to release the Kayelekera Uranium Mine agreement and a contract with Nyala Mining for a ruby project in 2016. The Malawi EITI Secretariat then gave the go ahead to publish the agreements online on the global contract repository www.resourcecontracts.org.

Since the contracts were published, I have worked with a private sector representative from Malawi’s multi-stakeholder group and developed a financial model of Kayelekera Uranium Mine based on the disclosed contract and public domain corporate filings with the support of OpenOil. The model shows the past and potential government take, the ways in which legally authorised tax incentives reduced government revenue but only marginally affected break-even price, and the necessary market price for production to restart at the mine. With this evidence, civil society is now better positioned in lobbying for improved fiscal regimes and has a deeper understanding of how uranium prices will affect the future outlook of the project.

Uranium and ruby contracts pave the way for petroleum

Following the publication of mining contracts, Oxfam Malawi launched an analysis of Malawi’s oil contracts (using data that was informally acquired as the contracts had not yet been officially made public) with Malawi’s EITI multi-stakeholder group and a number of other government officials. It was at this meeting that the Department of Mines and the newly formed Petroleum Secretariat confirmed that the agreements were public and they were willing to share them. A few weeks later, the PSAs were made available online in the repository.

Malawi’s oil contracts have now been assessed in greater depth. In April 2018, Oxfam Malawi published an analysis by Resources for Development of the revenue generating potential of the fiscal terms contained in the PSAs. Three sets of fiscal terms were analysed using hypothetical fields, namely, the terms contained in Malawi's signed contracts, those contained in Malawi's draft Model PSA, and those being considered for inclusion in the addendum to the signed PSAs. The hypothetical fields were drawn using examples from Kenya and Uganda, which are located in the same African Great Rift Valley.

Findings of petroleum contract analysis

The analysis shows that the signed PSAs result in a government take that is less than 60% with some very unusual fiscal arrangements. This is lower than the IMF recommended divisible revenue from a petroleum project, which is between 65% and 85%. Even though the proposed addendum would increase the government share, changes to fiscal terms do not enable Malawi to secure a larger share of the divisible revenue for highly profitable projects.

Malawi’s oil prospects are highly uncertain at present as exploration is in the preliminary stages. Nevertheless, a well-designed fiscal regime is necessary now as the PSAs cover development and production and not just exploration. Based on the analysis, civil society continues to call on government to make sure the addendum to amend the signed PSAs results in a fair share for Malawi. An analysis of the contracts may also help the Anti-Corruption Bureau investigate Mudzi Transformation Trust set up by Malawi’s former president, Joyce Banda. The Bureau is investigating payments made by oil companies to her trust when the initial PSAs were signed in what seems like a rush just before she was ousted in elections.

Contract transparency – what next?

Now that the agreements are public, it should be easier for government regulators to enforce the rules relevant to their areas of responsibility. It also means that civil society can better understand decision making and actions around the projects and alert the regulators if something does not seem right. From the company perspective, while this might seem threatening, experiences of contract disclosure elsewhere suggest that this added engagement can actually contribute to more trusting relationships, which in turn make operations run more smoothly.