Summary

Corruption is a pressing challenge for many resource-rich countries. According to the OECD Foreign Bribery Report, one out of five cases of transnational corruption occur in the extractive sectorHideOECD (2014), OECD Foreign Bribery Report . Twenty percent of the over 200 enforcement actions under the US Foreign Corruption Practices Act (FCPA) are linked to the extractive industry, the highest among all sectorsHideNRGI (2016), “Oil, Gas, Mining Remain Major Focus for FCPA Investigations” .

There is a shared view among EITI stakeholders that addressing corruption risks is implicit in the multi-stakeholder group’s (MSG) efforts to promote transparency and accountability by adhering to EITI Standard. However, the EITI’s role in tackling corruption is not always explicitly stated in national objectives for EITI implementation. In 2020, the EITI Board recognised the need for the EITI to clearly articulate its role in deterring corruption and provide support to MSGs to enable them to contribute to anti-corruption measures.

EITI reporting can shine a light on some of the areas most prone to corruption risks. For example, it could help to expose practices in natural resource governance that are vulnerable to abuse, expose suspicious deals and transactions, provide valuable contextual information at a national level, support citizens’ debate, monitoring and advocacy around resource governance, advance global norms and policies related to anti-corruption, and deter corrupt behaviour through transparencyHideAlexandra Gillies (2019), The EITI’s Role in Addressing Corruption .

This note aims to support MSGs by providing practical guidance and a step-by-step approach for defining the EITI’s role in mitigating corruption at the country level. The suggested steps include factors that MSGs could consider in undertaking their anti-corruption activities, as well as concrete examples of activities and considerations. Annexe A provides examples of how to apply these steps in specific areas of extractive sector management.

This guidance is not meant to be prescriptive nor does it aim to expand the scope of the EITI Standard. It outlines opportunities to better use existing EITI disclosures to strengthen anti-corruption efforts. It also includes topics in high-risk areas that are not currently covered by the EITI Standard, such as the energy transition, service contracting and local content. In using this guidance, MSGs are encouraged to consider their national context, taking into account the various types of corruption risks, key actors and legal frameworks in their country. This note also presents relevant tools designed by other institutions that can serve as frameworks for discussing these issues.

For the purpose of this note, the term “corruption” is defined as “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain” in accordance with Transparency International’s definition.

- The extractive sector is prone to corruption risks because of the scale of revenues it generates and the players and ownerships involved, as well as the complexity of the sector. The EITI has a role to play in addressing these risks through its disclosure requirements and multi-stakeholder approach.

- MSGs are encouraged to identify the most important corruption risks in their countries. In doing so, they will be able to formulate objectives for EITI implementation that address these corruption risks and to define the role that they should play in meeting these objectives.

- MSGs have the discretion to determine the scope of their work on anticorruption. One way of doing this is to approach their ongoing activities with an explicit anti-corruption lens, for example on licenses, beneficial ownership, contract transparency and state-owned enterprises.

- MSGs are encouraged to use existing tools and mechanisms to further their anti-corruption work. For example, EITI Reports could include complementary data to help identify red flags, Validation assessments could surface deviations from regulatory frameworks, and work plans could be used to monitor how the EITI is creating impact on corruption mitigation.

- MSGs could opt to tackle corruption issues on known areas of risk that are not covered by the EITI Standard, such as service contracting, energy transition or local content.

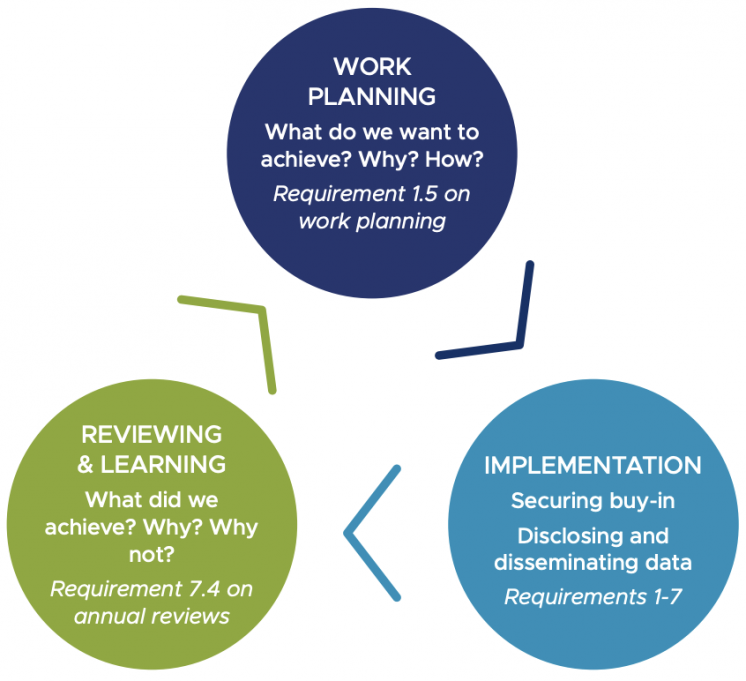

Overview of steps

When developing an anti-corruption action plan, MSGs are encouraged to follow the steps below.

| Steps | key considerations | examples |

|---|---|---|

|

Step 1: |

|

|

|

Step 2: |

|

|

|

Step 3: |

|

|

How to develop an anticorruption action plan

Step 1: Assess corruption risks and formulate objectives to address them

EITI implementation should be aligned with national priorities for the extractive industries. MSGs are required to identify these national priorities and ensure that their objectives for EITI implementation are aligned with broader reforms.

Key questions to consider:

1. How can MSG activities link to broader national reforms on anti-corruption?

MSGs are encouraged to build a general understanding of a country’s anti-corruption efforts and consider reaching out to law enforcement agencies, anti-corruption commissions, Supreme Audit Institutions, journalists and other actors to discuss how EITI implementation could link to these efforts. MSGs could present the information available in EITI reporting to relevant actors and promote exchanges about its use.

Indonesia and Nigeria: Linking EITI implementation to national reforms

Indonesia’s anti-corruption framework includes a reference to the EITI. Its MSG’s work plan also links existing national strategies with EITI implementation. It pays special attention to beneficial ownership reform as a key transparency gap and a concrete anti-corruption measure and to working in partnership with the national Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK).

EITI Nigeria capitalised on strong political will and high-level engagement on Open Government Partnership (OGP) commitments on beneficial ownership to progress its plans on establishing a register of beneficial owners of extractives companies. The MSG’s 2018 work plan included this as a priority area, and in 2020 the Companies and Allied Matters Act (CAMA) was approved which provided a legal basis for Nigeria’s beneficial ownership register. Currently, information on the beneficial owners of companies is required for license renewals and license applications processes. Furthermore, one of the key objectives of the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA), enacted in 2021, is to promote transparency, good governance and accountability in the administration of petroleum resources, with clear disclosure provisions including the establishment and maintenance of public registers for licenses and beneficial ownership.

2. Which stages of the extractive industry value chain are most prone to corruption issues?

MSGs could further define the scope of their work by identifying potential corruption risks to prioritise action. In doing so, MSGs may focus on specific stages of the extractives value chain to identify transparency gaps.

For example, MSGs could identify corruption risks in licensing by:

- Examining the bidding process for licenses awarded;

- Evaluating regulations to identify loopholes that could be abused;

- Evaluating the extent to which inadequate systems and lack of transparency in regulations make it possible for political capture and conflicts of interest to occur.

The scope and priority areas for the assessment should be informed by the prevailing corruption issues in the sector and country. MSGs may wish to draw on existing practical tools to identify corruption risks in each stage of the sector’s value chain.

The Mining Awards Corruption Risk Assessment (MACRA) Tool

Transparency International’s MACRA Tool has been used in over 20 countries. An abridged version, which can be completed within four months, helps users identify and assess the underlying risks and causes of corruption in license allocations which can undermine the lawful, compliant and ethical awarding of mining licenses, permits and contracts. The tool helps users to:

- Identify the vulnerabilities and strengths in the mining awards process;

- Identify and assess the corresponding corruption risks;

- Validate and prioritise corruption risks for action;

- Translate research into action.

Corruption diagnostic tool

The corruption diagnostic tool, developed by the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI), provides concrete steps and guidance to:

- Gather evidence and convene consultations to identify the forms of corruption most likely to negatively impact their country’s extractive industries;

- Diagnose the causes of these forms of corruption;

- Build an evidence-based anti-corruption action plan, focused on preventing future corruption.

3. Which commodities and sub-sectors are most vulnerable to corruption?

The nature of a commodity could influence its level of corruption risk. For example, gemstones are particularly prone to smuggling because of the ease of transportationHideGlobal Witness (2021), Jade and Conflict: Myanmar Vicious Circle . Another factor that could affect the level of risk is how the commodity is priced. For example, commodities subject to dynamic pricing are more prone to trade-related corruptionHideFor an example of how dynamically priced commodities are prone to trade-related corruption, see OpenOil (2018), EITI Commodity Trading in Indonesia . In some instances, fiscal frameworks could inadvertently incentivise revenue leakages through small-scale artisanal mining (ASM) regulation gapsHideSee EITI (2018), Panning for data: Artisanal and small-scale mining in EITI countries .

Furthermore, as the global transition to cleaner energy increases demand for critical minerals, paying particular attention to corruption risks related to these minerals can help build a relevant anti-corruption strategy that complements national priorities.

4. Are there policies and practices that heighten corruption risks?

EITI Reports could expose practices in natural resource governance that are vulnerable to abuse. They could reveal weaknesses in government systems that increase the likelihood of corruption to occur. For example, Myanmar’s 2015 EITI Report revealed that the country’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) retained about half of all extractive sector revenues in opaque accounts. A study commissioned by Myanmar’s EITI chapter found that 98% of gemstone permits operate “without oversight and permit-holders free to choose how they produce, what they declare, and whether or not this goes through formal channelsHideAlexandra Gillies (2019), The EITI’s Role in Addressing Corruption.”

Vested interests could be a deterrent to good governance. Government officials might also be unevenly enforcing fiscal, operational or environmental and social obligations to politically connected companies. MSGs could opt to focus on these issues to evaluate how policies are implemented in practice.

Zambia: Identifying gaps and corruption risks

Zambia’s 2018 EITI Report provided detail on an inquiry by the auditor general, which exposed several questionable practices, including the award of mining licenses to unqualified companies, illegal mineral exports, tax evasion and violations of environmental obligations. This investigation was prompted by the findings of Zambia’s 2016 Validation Report and the findings resulted in the government cancelling nearly 900 licenses.

5. Are there areas of extractive management that are at high risk of corruption, that are not covered by the EITI Standard?

To create more impact, MSGs could consider evaluating or identifying other areas that are prone to corruption. One example is service contracting. Oil and mining companies typically outsource most of their exploration and production work to a wide range of contractors. NRGI estimates that these contracts are worth somewhere between USD 745 billion and USD 1.3 trillion a yearHideIbid . However, along with bribery, subcontracting is vulnerable to self-dealing among political elites, contract inflation, collusion and tax evasion.

To address this, MSGs could consider analysing the corruption risks and transparency needs in the sector.

MSGs have the discretion to define their objectives related to anti-corruption based on the considerations explained above. Some examples of objectives that MSGs could adopt include:

- To identify gaps in revenue collection systems that facilitate corruption;

- To address legal loopholes in sectoral laws that enable corruption;

- To detect risks in licensing procedures of specific commodities or in particular subnational jurisdictions;

- To address risks in the undervaluation or illegal smuggling of specific commodities;

- To analyse and cross reference beneficial ownership data to detect red flags and potential conflicts of interest in license awards.

Step 2: Develop an activity plan

After the MSG has assessed the corruption risks that they wish to tackle, they could develop an activity plan to meet their objectives related to anti-corruption. Work plans must include measurable and time bound activities to achieve the agreed objectives (Requirement 1.5). EITI guidance on developing work plans provide examples on how anti-corruption measures can be integrated into EITI implementation.

Albania, Mongolia and the Philippines: Integrating anti-corruption in EITI work plans

Mongolia’s 2021 work plan explicitly includes addressing corruption as one of Mongolia EITI’s objectives and outlines specific activities to meet this objective, including a pilot on managing risks using NRGI’s diagnostic tool for corruption risks. Similarly, the Philippines’ 2021 work plan includes conducting an analysis using NRGI’s corruption tool.

Albania’s 2021-2022 work plan aligns EITI implementation with the national anti-corruption agenda. It highlights the MSG’s role in raising awareness and conducting outreach activities, as well as the need to reform national legal frameworks to strengthen natural resource management

In identifying activities, MSGs are encouraged to consider which measures are likely to have an impact. A useful framework for developing an action plan is to categorise measures or approaches according to the objectives set by the MSG. For example, NRGI’s anti-corruption diagnostic tool illustrates that some activities could focus on enhancing transparency to facilitate oversight and deter wrongdoing, while other activities could focus on strengthening oversight and participationHideNRGI (2021), Diagnosing Corruption in the Extractive Sector: A Tool for Research and Action . Other categories of measures could include promoting integrity through robust and well-enforced anti-corruption measures, reforming institutional and regulatory processes, increasing fair competition, strengthening the enforcement of rules, and addressing foreign enablers.

Examples of activities:

- Technical studies on the types of risks in a particular sector/commodity; studies to evaluate legal or regulatory loopholes.

- Use of diagnostic tools such as NRGI’s corruption diagnostic tool and Transparency International’s Mining Awards Corruption Risk Assessment (MACRA) tool as described under Step 1.

- Formulation of recommendations/safeguards against corruption. MSGs could issue policy recommendations for dissemination to government officials (including parliaments) based on corruption risks they have identified.

- Capacity building and awareness raising. MSGs are encouraged to conduct capacity building activities on corruption risks in the extractive sector and the role of EITI in corruption mitigation. They could also lead trainings on how to effectively use and analyse data to inform anticorruption efforts and detect red flags. These could focus on specific requirements of the EITI Standard, especially on highly technical requirements related to SOE transactions, in-kind revenues, barter and infrastructure arrangements or beneficial ownership.

- Analysis of corruption cases. MSGs could analyse corruption cases to better understand how corruption occurs in actual practice, identify who are the actors, and highlight what types of transactions are vulnerable to risks. This could aid ongoing investigations or could inform policy recommendations.

- Regular consultations. MSGs could use regular meetings and outreach activities to conduct consultations with stakeholders regarding the efficiency of their anticorruption programmes. For example, companies could consult communities and indigenous peoples during outreach to detect corruption risks in the implementation of their social projects and in conducting due diligence. Governments could use outreach activities to report and explain results of licensing processes to the wider public to address perceptions of corruption. Civil society could demand a standing item in the MSG’s agenda to monitor results of anti-corruption plans of regulatory agencies and companies.

Key questions to consider in developing an action plan:

- Do the activities directly contribute to the desired objectives? In deciding on activities, the MSG could consider what types of activities would lead to outputs or outcomes that would support their objectives. For example, if the end goal is to mitigate risks in the licensing process, the MSG could consider raising awareness among internal and external regulators of the relevant agency about how corruption occurs at every stage of the licensing process. MSGs could also complement this work by mapping corruption risks and conducting workshops or focus groups to discuss the findings of the mapping exercise. Where there are recommendations from EITI Reports, Validation and other technical studies related to combatting corruption, the MSG could consider including these recommendations in the action plan.

- Could activities in the EITI work plan include an anticorruption component? The MSG’s work on anti-corruption could be integrated into existing activities planned for EITI implementation, including licensing, beneficial ownership, contract disclosure, revenue disclosure, social and environment expenditures, mainstreaming, commodity trading and energy transition. Applying an anti-corruption lens to any of these policy areas could help MSG link their work to national priorities.

- EITI reporting - EITI Reports and disclosures of extractives data are an important part of MSG work plans and provide valuable contextual information that helps increase citizens’ understanding of the sector. MSGs should consider how EITI reporting could be used to document corruptionrelated information. For example, in 2015, NRGI used EITI Reports to better understand the Nigerian national oil company’s oil trading business in its research on corruption risksHideAlexandra Gillies (2019), The EITI’s Role in Addressing Corruption .

- Use of EITI disclosures - MSGs could also ensure that anti-corruption actors are using EITI disclosures to advance anti-corruption efforts. MSGs could draw from NRGI’s study on how anti-corruption actors could use data disclosed in EITI ReportsHideNRGI (2021), How Can Anticorruption Actors Use EITI Disclosures? and recommendations memorandumHideNRGI (2021), Recommendations for Strengthening the Role of the EITI in the Fight Against Corruption which provide good examples of how MSGs can analyse EITI Reports with an anti-corruption lens. One concrete example is triangulating the different sets of data on production, exports, revenues social expenditures, contracts and beneficial ownership to identify illicit practices such as underpayment of revenues and fees, smuggling and conflicts of interest.

- Are there potential constraints? If so, what measures would address them? Engaging in anti-corruption work in a more explicit way could be met by resistance by various actors within and outside of the MSG. Anticipating this possibility at the outset would help the MSG address constraints. For example, a clear articulation of what the EITI seeks to address could help in securing wider support for the MSG’s anti-corruption efforts. Capacity constraints should also be mapped, especially with respect to understanding risks occurring in complex transactions where not all parties have the same access to information, such as in commodity trading or contract negotiations.

- Has the role of the MSG been defined and articulated and have responsibilities for the various activities been assigned to relevant stakeholders? After identifying the gaps and defining the objectives for the MSG’s anti-corruption work, MSGs are encouraged to further define their role in meeting these objectives. Meeting a broad objective entails thinking through different types of interventions. In defining its role, the MSG could consider its access to anti-corruption actors. This may in some cases require involvement of stakeholders beyond those represented in the MSG. Whether the MSG chooses to play a more hands-on role (e.g. formulating policies and lobbying for polices to be implemented) or a facilitating role (e.g. fostering inter-agency cooperation), engagement with key stakeholders could help the MSG achieve its objectives. In engaging companies, MSGs could consider addressing the issue related to risks involving agents and intermediaries. In identifying which stakeholders to engage, MSGs are encouraged to include women’s rights organisations and marginalised groups, as well as indigenous populations and ethnic minorities, which could help ensure that issues on potential vested interest are scrutinised.

Indonesia, Mongolia and Senegal: Engaging key actors

In some countries, such as Mongolia and Indonesia, anti-corruption actors participate in MSGs or have close engagement with MSGs. In these cases, such actors may be able to play a more active role in using EITI data to aid investigation. In some cases, MSGs may play an advisory role in drafting reports to inform policies. Senegal’s MSG engaged closely with the government’s Fiscal Investigation Center to prepare a report on the extractive sector, as well as with the national anti-corruption agency to provide inputs to the National Anti-Corruption Plan.

Some examples of the different roles that MSGs could play when they engage in anti-corruption issues include:

- Supporting citizens’ discussion, monitoring and advocacy. MSGs could serve as a platform for different stakeholders to discuss, monitor and evaluate corruption risks. For example, the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s MSG followed up on concerns revealed in EITI Reports and raised by external stakeholders about certain payments to government that were not shown to have been paid to the Treasury. The complex nature of the extractive sector makes it challenging for the public to fully comprehend how corruption occurs. The MSG could provide platforms to discuss the different types of corruption in the sector to stimulate public debate. In some cases, stakeholders may be unaware of existing EITI data or how to translate data into action and advocacy on anti-corruption. MSGs are encouraged to consider engaging anti-corruption actors (competent authorities, anti-corruption bodies, corporate investigators, investigative journalists, CSOs and community leaders and private groups that focus on integrity work) to introduce EITI data and strengthen techniques and methodologies to use existing information.

- Analysing current EITI disclosures and providing recommendations to strengthen government systems. Publishing EITI Reports should not be an end in itself; MSGs are also expected to provide recommendations to inform extractive sector policies. While the quality of these recommendations has improved over time, MSGs have rarely taken up the opportunity to provide recommendations that explicitly tackle corruption issues. For example, not all EITI Reports include an assessment of deviations from licensing procedures, despite this being required by the EITI Standard (Requirement 2.2.a.iii.iv).

Although many countries have publicly disclosed beneficial ownership data and contracts, efforts by MSGs to analyse this information are minimal. In conducting such analysis, MSGs could draw from NRGI’s study on how anticorruption actors could use data disclosed in EITI Reports which illustrates how data from these reports could inform anti-corruption efforts. - Demanding or disclosing complementary data. Data disclosed in EITI Reports is often inconclusive and rarely points to anomalies. Complementary data is needed to draw conclusions on whether a particular transaction was tainted with corruption. The MSG could play a role in demanding data from authorities that are not typically engaged in the EITI process to disclose information that would complement EITI data. Examples include data related to campaign financing of public officials or asset declarations of politically exposed persons. Nigeria EITI is exploring the possibility of connecting beneficial ownership data with financial disclosures of public officials, replicating of a project on beneficial ownership piloted by the EITI in ColombiaHideDirectorio Legislativo and EITI, “Joining the Dots” . MSGs could also consider expanding the scope of EITI reporting to include other areas of risks, such as service contracting, or risks in the renewable energy sector.

- Facilitating inter-agency cooperation. In many countries, the EITI’s strength is its ability to convene agencies and agree on common objectives and recommendations for extractive sector governance. MSGs could involve agencies beyond the MSG that support anti-corruption reforms.

This has proven to be effective in engaging various stakeholders on beneficial ownership reforms where MSGs have engaged with new actors such as ministries of law, company regulators, central banks, anti-money laundering councils and other law enforcement agencies. The same approach could be used for MSGs’ anti-corruption work. MSGs could engage prosecutors, corruption eradication commissions, the judicial branch, parliament and ombudspersons to facilitate inter-agency cooperation. Furthermore, MSGs could contribute to discussions to aid corruption investigations by providing data-based evidence or expert advice. - Does the activity plan reinforce and leverage the strengths of the EITI national process? MSGs are encouraged to reinforce EITI processes, responsibilities and activities to support anti-corruption work. MSGs could evaluate the strengths of EITI implementation in their country, as well as existing opportunities to link EITI processes with anti-corruption initiatives. This work can span various areas covered by EITI implementation, including:

- Subnational reporting: If there are robust subnational processes, the MSG could consider playing a role in facilitating discussions on corruption detection and mitigation at the subnational level on certain requirements of the EITI Standard.

Colombia: Using disclosures on social expenditures to deter corruption at the local level

National government stakeholders who were consulted during Colombia’s Validation welcomed further disclosures of companies’ social contributions at the local level, to deter local government corruption. The MSG could play a role in working closely with local authorities to develop a multistakeholder approach for local disclosures, especially in light of the fact that Colombia had fully met the EITI’s requirements on disclosing social expenditures (Requirement 6.1.a).

- Systematic disclosure: Countries that are advanced in systematic disclosure could explore how their efforts to digitise data disclosure could be linked to anti-corruption measures.

Indonesia: Linking anti-corruption efforts with open data reforms

In Indonesia, the Corruption Eradication Commission has linked its efforts to combat corruption with the national plan for digitisation. To complement this effort, the MSG in Indonesia is leading the effort to systematically disclose extractives data through the EITI process under Requirement 4.1.a.

- Contract transparency: The progress in meeting the EITI Requirement 2.4.a. on license registers and contract disclosure could also be used to mitigate corruption

Ghana and Senegal: Using progress on contract disclosure and beneficial ownership to improve sector governance

Senegal is the first country to go beyond the EITI’s requirements on full contract disclosure. The MSG could take advantage of this progress by playing a role in monitoring compliance with contractual obligations. Building on Ghana’s progress in beneficial ownership reforms, the MSG is playing a role in improving inter-agency coordination and strengthening capacities of anti-corruption actors. Ghana’s 2021 work plan aims to “strengthen the reporting or disclosure process of natural persons behind the ownership of corporate bodies with a view to reducing corruption and improving natural resource governance” under Requirement 2.5. Efforts are underway to work with competent authorities as well as journalists, civil society organisations and citizens to verify and use beneficial ownership data. Ultimately, the use of Ghana’s beneficial ownership register, existing petroleum and minerals contracts and GHEITI’s financial disclosures are critical to addressing government priorities and informing public debate on corruption and illicit capital flight.

- Has a timeframe for implementing the activities been drawn up? In drawing up a timeframe for implementing activities, MSGs could consider key opportunities in their broader national reform processes, such as approval of bills for legislation and formulation of national strategic development plans, or when their governments sign up for international commitments related to anti-corruption. In determining milestones for their activities, MSGs could also reference their Validation schedule. During Validation, countries are assessed on the outcomes and impact of EITI implementation as well as the level of disclosure.

- Have resources for the activities been identified and estimates of costs and funding? Requirement 1.5 of the EITI Standard requires that work plans be fully costed. Where there are funding gaps, MSGs should ensure that resources are available to implement work plan activities. MSG should consider available resources and tools to implement some of these activities. EITI Reports and Validation assessments could be valuable sources of information on corruption risks and deviations from legal procedures. MSGs could also look at data from government agencies, SOEs and companies, industry analysts and international financial institutions. MSG are encouraged to assess context, adapt processes and tailor existing tools to address their specific needs.

Step 3: Monitor results

Monitoring frameworks are a tool to help MSGs strengthen the link between overall objectives (Step 1) and anti-corruption activities (Step 2). By detailing activities and their expected outcomes and regularly reviewing monitoring data, MSGs can strengthen implementation, demonstrate value and build support. Step 3 looks to align monitoring frameworks with existing EITI processes, which can lower the burden of preparing for Validations, annual work planning and reporting and make the outputs of those processes more useful to MSGs in supporting anti-corruption outcomes and reforms.

Key questions:

1. What should be monitored and how?

Evidence collected through monitoring can serve different purposes:

- Strong monitoring data can help national secretariats and MSGs learn and strengthen implementation, so that MSGs use limited resources more efficiently, and improve the results of implementation.

- Monitoring data can help link EITI activities to broader reforms and engage with national stakeholders and decision-makers. Demonstrating the value of EITI activities for anti-corruption can help national secretariats gain access to resources, partnerships and political support.

- Monitoring data can help to access support and build relationships with partners, strengthen the credibility of MSG activities and lay the groundwork for demonstrating results.

Identifying the most important ways in which national secretariats and MSGs want to use evidence will help to determine how to best monitor progress towards the objectives identified in Step 1.

2. How to select data sources and indicators?

Several different types of monitoring data can help track progress towards anti-corruption objectives, including public opinion survey data, administrative data on corruption prosecutions and investigations, market statistics, media monitoring or downloads from beneficial ownership registries. This data can, in turn, be used for different kinds of monitoring indicators, both qualitative and quantitative, aligned with the factors for consideration in Step 2. Regardless of which kind of monitoring data and indicators are best for tracking activities in the EITI work plan, it is important to plan how that data will be collected and stored.

3. How to identify appropriate roles and expertise?

Consider identifying one person to be a monitoring focal point with overall responsibility for monitoring data, to make sure it is collected in a timely manner and safely stored. This is especially important when monitoring data will be collected regularly from several organisations or government agencies.Making these types of decisions can be challenging without monitoring and evaluation expertise, which might not be available in the MSG. Consider recruiting such expertise in helping to design monitoring frameworks, either locally through universities or national statistical offices, or through international consultants. The EITI International Secretariat can also offer recommendations on how to access appropriate expertise.

4. How to align monitoring with EITI processes?

While deciding how to collect monitoring data, MSGs could consider how to align monitoring activities with existing EITI processes. This can help to avoid duplication of efforts and strengthen EITI planning, reporting and Validation. Consider processes such as:

- Work planning. Ideally, the activities in work plans will already be described in terms of results chains, with specific inputs, outputs and outcomes. Identify the most appropriate indicator for each stage in the results chain, for each key activity. When doing so, consider whether monitoring indicators satisfy the “SMART” criteria (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-bound), which can help ensure that will make the data that is collected easier to understand and use.

- Validation. When defining what to measure, it can also be useful to consider the data collection templates that are used for EITI ValidationHideSee EITI, “2021 Validation model templates” . These templates are approved by the EITI Board and MSGs are encouraged to use them to support regular oversight of EITI implementation. In particular, the “Outcomes and impact template” suggests specific types of results that will be explored in Validation. Aligning monitoring frameworks with this template can facilitate and strengthen annual reporting and Validation processes.

- Annual reporting. Monitoring data should be reviewed and evaluated on an annual basis as part of the review process (Requirement 7.4). Monitoring frameworks provide a bridge between the annual workplan and annual progress reports that help to review and strengthen implementation every year.

5. What are the opportunities to learn from monitoring and review?

In addition to conducting an annual review and reporting, monitoring data should be reviewed regularly to create opportunities to learn and strengthen implementation. How often will depend on the national context, but quarterly reviews of some activities can enable MSGs to identify when activities are stalled or need to be adjusted.

MSGs should consider whether activities are leading to the intended outputs and outcomes described in EITI work plans. This question will be best answered when it is asked in an inclusive forum. Using the MSG and working groups to review monitoring data will help to ensure that it is useful, and that gaps and improvements are identified and addressed.

Addressing corruption through monitoring, evaluation and learning

Monitoring approaches to anti-corruption activities in EITI implementation

Nigeria: The 2019 Work Plan Monitoring and Evaluation Report includes several anti-corruption activities that are aligned with the national objective of anti-corruption reforms, such as integrating a Corruption Risk Assessment in the Nigerian Ports - Implementation of Integrity Plan and updating anti-corruption agencies’ action plans for response to audit reports. These activities are aligned with specific time frames, key performance indicators and outcomes.

Mauritania: The 2018 Monitoring and Evaluation was developed based on the GIZ Framework for EITI Monitoring and Evaluation, and outlines links between specific activities, results and long-term impacts, including the “Fight against corruption and increase transparency” (result 13.3).

Philippines: An impact assessment conducted by the UP Statistical Center Research Foundation in 2019 used a public opinion survey to assess stakeholder expectations regarding the EITI, and the EITI’s role in fighting corruption in particular. This was conceptualised according to a theory of change whereby stakeholder expectations influence the perceived quality and value of the EITI, as well as the EITI’s overall impact.

Other national monitoring frameworks for EITI implementation are also relevant, even though they might not be specifically focused on anti-corruption activities and objectives:

Ukraine: Ukraine EITI produced a monitoring and evaluation framework in August 2020. Developed with support from international partners, the framework sets out recommendations and indicators to better assess the EITI’s impact on national reforms, broken down in four categories: EITI governance and administration, development of a dialogue platform for strategic ideas and proposals, expansion of the EITI and EITI-related activities, and strengthening partnerships between local governments, companies and civil society.

Germany: The Germany EITI uses a traffic light system to monitor progress on specific activities in its work plan and publishes that overview on the D-EITI website.

Further resources

- Transparency International, Using the EITI Standard to combat corruption

- OECD, Corruption in extractive value chain

- OECD, How to address bribery and risks in mineral supply chains

- NRGI, Twelve red flags: Corruption risks in the award of extractive sector licenses and contracts

- NRGI, Beneficial ownership screening: Practical measures to reduce corruption risks in extractives licensing

- U4, Anti-corruption in the renewable energy sector

- GIZ, Guideline for monitoring and evaluation of the EITI

- Global Integrity/UNDP, A users’ guide to measuring corruption

- U4/Transparency International, Approaches to monitor identified external corruption risks in development programmes

- World Bank, Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) of anti-corruption action plans