Summary

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) play important roles in exploiting natural resources and managing the extractive sectorHideA state-owned enterprise (SOE) refers to a company that is owned in whole or in part by the government. The roles of SOEs vary from country to country, and in the natural resource sector SOEs are often responsible for both commercial and non-commercial activities. They can be described as business-oriented majority government owned institutions that sell goods or services or manage state equity and keep their own balance sheets. See: IMF (2007) Manual of Fiscal Transparency. Section 1.1.4 “Relationships between the government and public corporations”. Pages 24- 29. . While some are commercial or operational companies —selling crude oil or raw minerals, managing state equity or participating directly in extractive operations — others are regulatory or administrative entities or instruments of economic or state development.

Many SOEs perform a mix of commercial and non-commercial duties. SOEs can generate significant revenue for the state, enable a government to exercise greater control over the sector, help improve local technologies and skills, manage exposure to energy transition risks, or address market failures by providing services that would not otherwise be provided by the private sector. State equity is also used by many countries to secure additional government take (beyond tax revenue) from extractive projects.

Governance of state participation and SOEs have considerable implications for public finances and the economy in general. Although some SOEs have made significant contributions to development and revenue generation, others have struggled with poor governance and corruption. Early results from EITI reporting and Validation have shown that although financial transactions related to state-owned companies have become more transparent, there is still a demand for improvement of transparency standards around SOE governance.

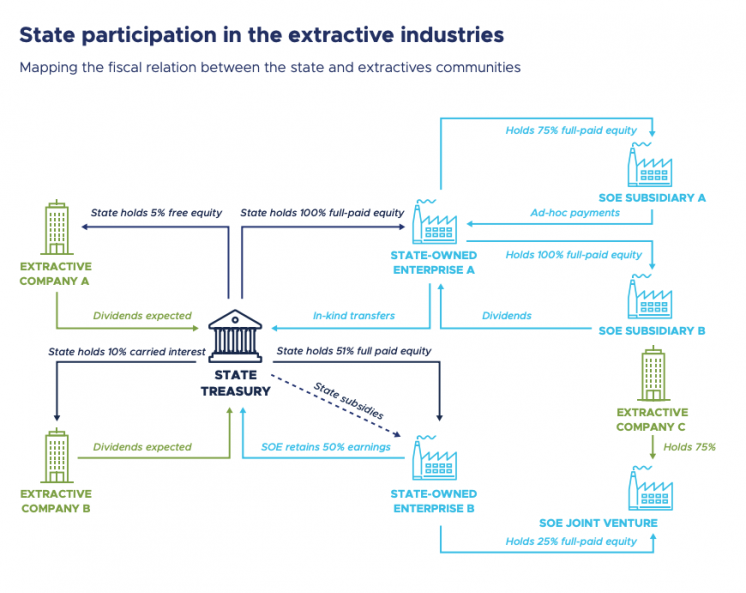

Requirement 2.6 of the EITI Standard requires that, where state participation in the extractive industries gives rise to material revenues for the state, the following information should be reported (1) an explanation of the prevailing rules and practices regarding the financial relationship between the government and state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and (2) the level of ownership by the government and SOE(s) in mining, oil and gas companies operating in the country, including those held by SOE subsidiaries and joint ventures.

This note provides guidance to multi-stakeholder groups (MSGs) on how to report on state participation as part of EITI implementation, offers a set of examples from implementing countries and outlines opportunities to strengthen the dissemination and use of data.

- What revenues can the state expect to collect from its direct and indirect participation in the extractive sector?

- How much is the state or SOE spending to meet the terms of its participation in the industry, what are they entitled to receive and how much is it actually receiving in revenues?

- What are SOE auditing rules and how are they complied with?

- Does the state or SOEs manage revenues collected from its particxipation in the industry in a transparent and sound way?

- Is the SOE a credible partner for a foreign company to enter in a business partnership with?

Overview of steps

| Steps | Key considerations | Examples |

|---|---|---|

|

Step 1: |

|

|

|

Step 2: |

companies, including minority interests and in SOEs?

|

|

|

Step 3: |

|

|

|

Step 4: |

|

|

|

Step 5: |

|

|

|

Step 6: |

|

|

|

Step 7: |

|

|

|

Step 8: |

|

|

|

Step 9: |

|

|

How to implement Requirement 2.6

The EITI International Secretariat recommends the following step-by-step approach to MSGs for reporting on state participation in the extractive industries. It is recommended that the findings from each step are documented by the MSG (e.g. in meeting minutes, scoping studies, EITI reporting or other disclosures).

In line with the default expectation that EITI implementing countries systematically disclose data required by the EITI Standard, the MSG should work with SOEs and government entities to ensure publication of information listed under Requirement 2.6 by the custodian entities. The EITI reporting process should review publicly available information, address any gaps in the existing data and analyse the data to contribute to improving the transparency and management of the sector around state participation.

Step 1: Agree a definition of state-owned enterprises (SOEs)

The MSG should first agree a definition of SOEs that is in line with the minimum required by the EITI Standard, taking into consideration the local context, including national legislation and relevant government structures. Requirement 2.6.a.i. states that “For the purpose of EITI implementation, a state-owned enterprise (SOE) is a wholly or majority government-owned company that is engaged in extractive activities on behalf of the government.”

The MSG’s definition should consider cases of companies holding extractives licenses, companies holding equity interests in other extractives companies (holding or asset-management company structure) and sovereign wealth funds.

The MSG may wish to consider the OECD’s definition of enterprises that are under the control of the state, either by the state being the ultimate beneficiary owner of the majority of voting shares or otherwise exercising an equivalent degree of control in agreeing its definition of SOEsHideSee OECD (2015), OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises, 2015 Edition..

Step 2: Comprehensively list all state participations in extractives companies and projects and describe the associated terms

The MSG should draft a comprehensive list of mining, oil and gas companies in which the government holds interests, either directly or indirectly through SOEs, including minority participations, SOEs and other forms of state equity, and companies incorporated in the country’s jurisdiction and abroad. The comprehensiveness of the assessment is important to ensure that state participations in extractives projects are not hidden through layers of corporate ownership.

This overview should be disclosed through relevant government systems, e.g. on the website of the ministry that manages state participation and/or SOEs. Information about shares held by SOEs themselves in extractive companies and joint-ventures should be disclosed directly through the SOEs’ publication platforms, where they exist. Where gaps in such disclosures exist, MSGs should ensure the information is disclosed through EITI reporting.

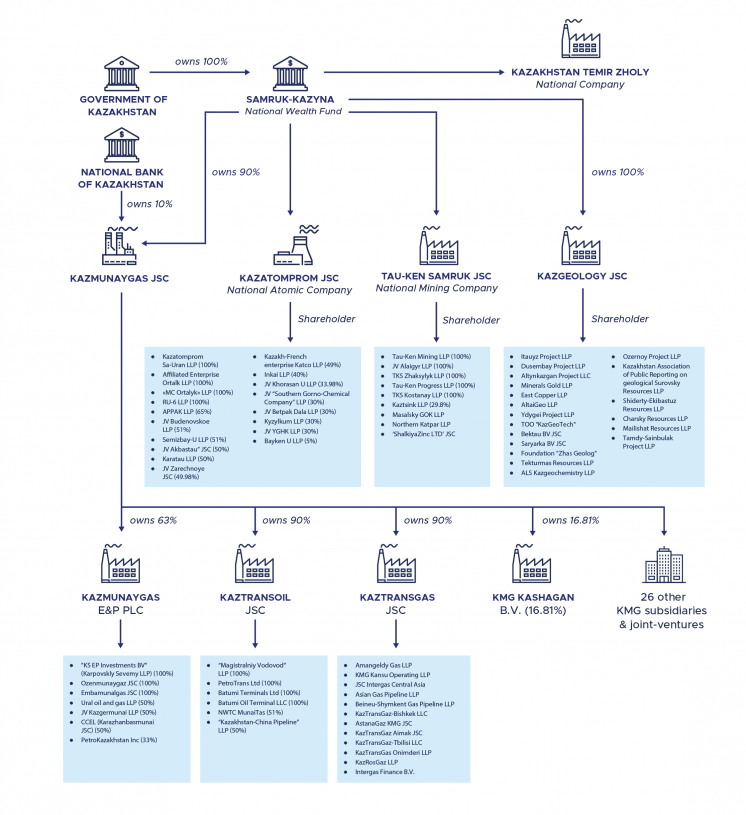

Kazakhstan: State ownership in the mining, oil and gas industry

The complexity of the structure of SOEs and subsidiaries calls for a comprehensive picture of all SOEs and their subsidiaries. Using existing disclosures to visualise such structures can help stakeholders get a better picture of state participation in the industry.

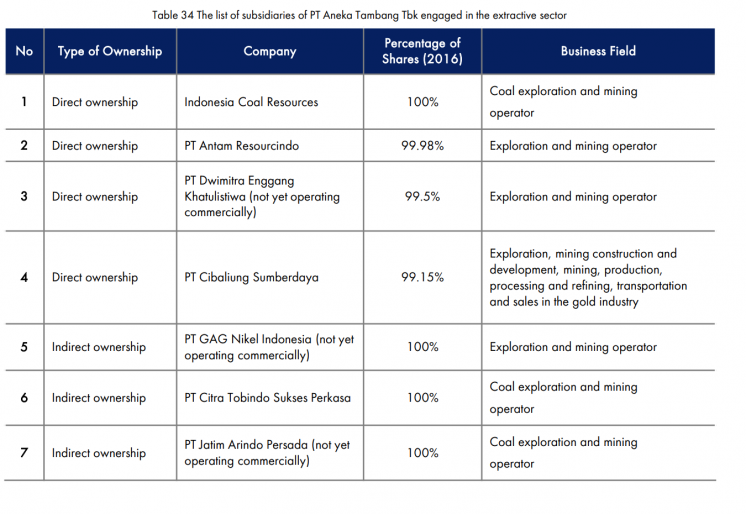

Indonesia: SOE subsidiaries

Below, SOE PT Aneka Tambang’s subsidiaries in 2016. The term “indirect ownership” should be better defined, with the structure of SOE subsidiaries and subsidiaries of SOE subsidiaries clearly listed.

The MSG should ensure that the terms associated with state or SOE equity in companies are clearly described, to help understand whether the state is responsible for future investment due to its ownership of equity in extractives companies, or whether its equity interest comes “free” (i.e. only with dividends but not requirement to fund that share of the company’s investments).

This information should be provided for all state equity ownership in the extractives, including those held by SOE subsidiaries, not only those considered material for EITI reporting. This should include details regarding the terms attached to the government’s or SOE’s equity stake, including their level of responsibility to cover expenses at various phases of the project cycle, e.g. full-paid equity, free equity, carried interest. The information on state and SOE participating interests in oil and gas projects should include information on the entitlements to production shares in line with the fiscal terms of the project. This information should be disclosed through government or company systems, where possible, with EITI reporting addressing disclosure gaps.

The terms associated with equity determine the duties and responsibilities of the shareholder. For instance, they define the shareholder’s (state’s or SOE’s) level of responsibility for covering expenses at various phases of the project cycle. They can consist of:

- Full equity: Equity on commercial terms. The shareholder is responsible for cover its share of expenditures (opex and capex) in line with its equity interest.

- Free equity: The state’s or SOE’s responsibility for covering its share of expenditures (opex and capex) in line with its equity interest is covered by the operator. The state’s or SOE’s equity is in effect ‘free’, since the state or SOE does not pay for its equity interest.

- Carried interest: The state’s or SOE’s responsibility for covering its share of expenditures (opex and capex) in line with its equity interest is covered by the operator during the development phase. The operator is then reimbursed once the project is operational/profitable. The state’s or SOE’s equity interest is in effect ’carried’ by the operator.

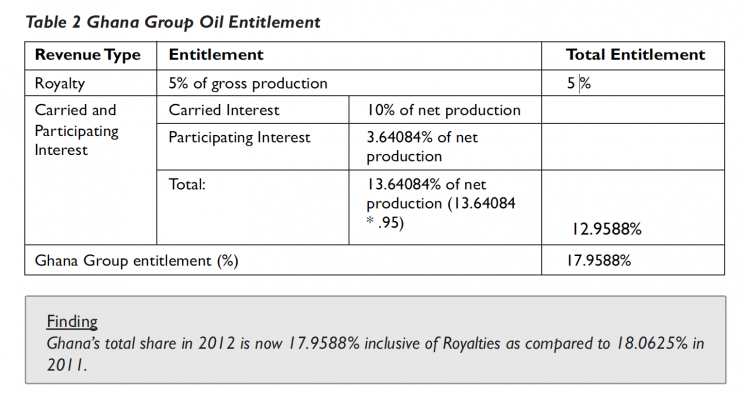

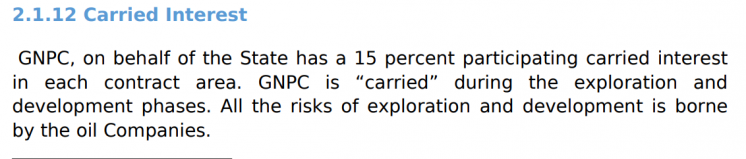

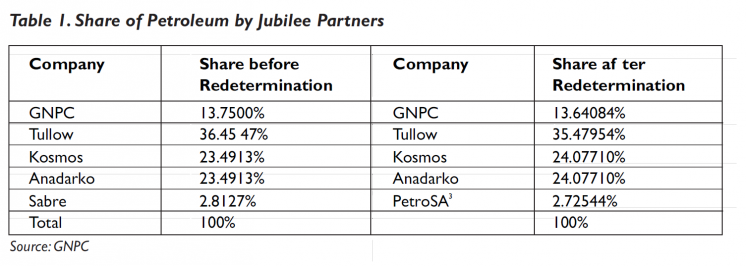

Ghana: Carried interest

Below, an example of disclosure of carried interest, where investment is covered by operator and subsequently reimbursed.

This shows the terms associated with SOE Ghana National Petroleum Corporation (GNPC) equity. The terms of the state’s participation in each PSC are described on the Petroleum Register.

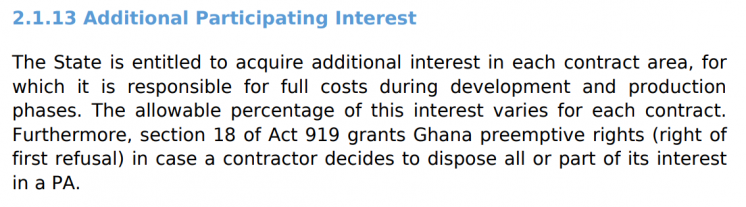

Philippines: Terms attached to SOE equity

Below, an example of disclosure of free equity, where the partner firms cover all project expenses on behalf of government. There is no requirement for SOE Philippines Mining Development Corporation (PMDC) to fund its equity interest.

Step 3: Describe any changes in state participation in the year under review

The MSG should identify any changes in state ownership of interests in extractives companies and projects in the year under review. Transparency in changes in state participation is key to understanding acquisitions and sales by the state and SOEs in the extractive industries, the valuation of state assets, whether transactions were undertaken on a commercial basis, and whether transfers of state assets to extractive companies were done with or without compensation. For each change in state ownership in the year under review, EITI reporting should indicate the corresponding terms of the transaction, including valuation and revenues.

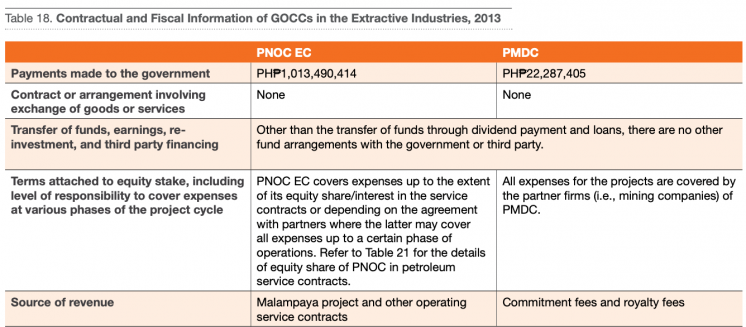

Indonesia: Changes in SOE ownership

2016 ownership changes in national oil company PT Pertamina’s working areas.

Ghana: Changes in state participation

The PIAC (Public Interest and Accountability Committee) reports in detail any change in state participation with implications for GNPC’s oil revenues.

Step 4: Assess the materiality of SOEs’ revenues and payments to government

The MSG should define the material SOEs for the purpose of EITI reporting. This means that the MSG has the flexibility to agreeing what constitutes a material SOE and which SOEs should be required to disclose information, by agreeing a materiality threshold. MSGs are encouraged to consider the non-commercial functions of the SOE in determining the materiality threshold.

Drawing on the comprehensive list of state participations in the mining, oil and gas sectors (Step 2), the MSG should refine a list of companies meeting the MSG’s definition of SOEs (Step 1). For each of the SOEs, the MSG should source from relevant government ministries or the SOEs themselves the value of:

- revenues collected from extractives companies,

- transfers in cash or in-kind to government entities.

By ranking all of the SOEs by value of their transfers to government, the MSG could consider setting a materiality threshold for selecting material SOEs that strikes a balance between comprehensiveness of disclosures and relevance of the information.

Non-financial factors can also help MSGs determine which SOEs are required to disclose information. In Iraq for instance, upstream oil and gas SOEs do not make financial payments to government, but are material given that they are involved in in-kind transfers and receive material transfers from government. MSGs could also take a risk-based approach to selecting SOEs to be included in the scope of disclosures in addition to those making material payments, considering which sub-sectors or commodities may be prone to governance risks or be of particular public interest.

The MSG should conclude on a list of SOEs considered material for EITI reporting in the year under review. On this basis, the MSG will need to describe the financial relations between SOEs and the government for those SOEs deemed material (Step 4).

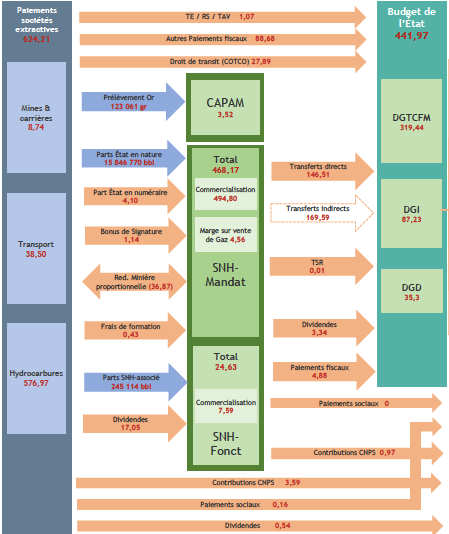

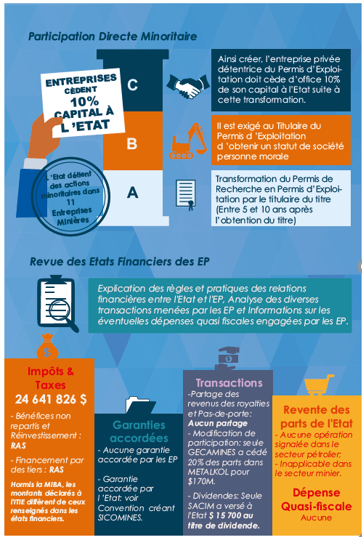

Cameroon: Distinguishing the SOE’s two roles on behalf of the state

The state-owned oil company Société Nationale des Hydrocarbures (SNH) reports figures clearly distinguishing between its role on behalf of the state (SNH Mandat) and its own account (SNH Fonctionnement). The materiality of revenues collected by SNH Mandat and SNH Fonctionnement are highlighted in the red box below.

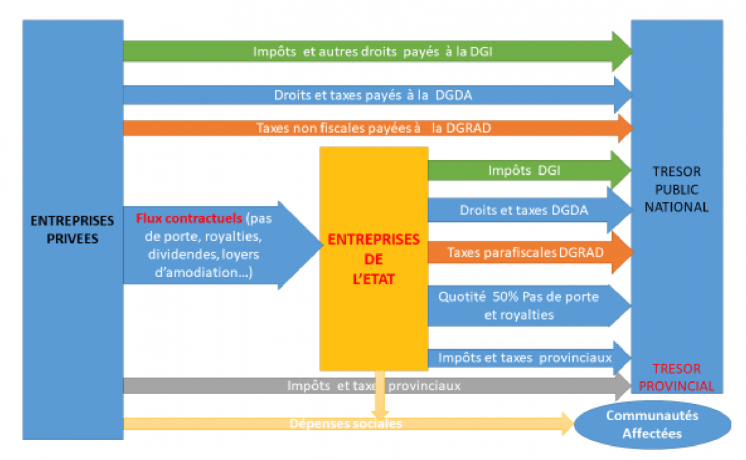

Democratic Republic of the Congo: Assessing SOE materiality

A review of the regulatory framework (laws, regulations and company statutes), as well as revenues and payments in the year under review, should be the basis for an assessment of SOE materiality. SOEs collect a range of non-tax revenues and make several tax and non-tax payments to government.

Step 5: Describe the statutory financial relations between SOEs and government

Relevant government entities and SOEs should disclose information on the prevailing rules and practices regarding the financial relationship between the government and SOEs, as well as between SOEs and SOE joint-ventures and subsidiaries.

Such information can be summarised through EITI reporting and form the basis for recommendations that feed into reforms where necessary and inform decisions around the sector. For example, in Myanmar, the government has focused on reforming the SOEs’ statutory rights to retain a significant share of earnings (up to 50% of oil and gas revenues) while receiving government subsidies. Similarly, in Senegal, the question of PETROSEN’s statutory rights to secure third-party financing will be key to developing the country’s large gas reserves.

The MSG should review the legislative and regulatory arrangements for state participation in the extractive industries. Based on an overview of the relevant laws, regulations, company statutes and other relevant documents, the MSG should describe the statutory rules related to:

- the transfer of funds between each SOE and the state, e.g. is the SOE expected to transfer dividends to the State, or does the SOE benefit from state subsidies? What are the rules governing the taxes, royalties, customs duties and other fiscal transfers to the government and the timetable for their settlement? Is there a clear dividend policy?

- the SOE’s retained earnings, i.e. the SOE’s right to retain revenues, both from its own operations and from operations conducted on behalf of government (e.g. commodity sales); What are the rules governing how the SOE can spend revenues collected from its operations?

- the SOE’s reinvestment, i.e. whether the SOE’s Board of Directors can decide on the SOE’s dividends; What are the rules governing what the SOE can spend its retained earnings on, whether operational, capital expenditures or retention in the company’s accounts?

- third-party financing for the SOE, possibilities to raise funding from a third source either through debt or equity; What if any rules govern the process by which SOEs may seek third-party financing?

- any other statutory transfer between government and the SOE.

The MSG could synthesise this analysis into more accessible language for a broader audience. This would create a strong basis for understanding the expectations for financial flows between SOEs and government, contextualising the rules and systems that determine transfers.

The MSG should consult and work with each SOE to ensure that the relevant regulatory texts are published (and, if possible, analysed) on their respective websites.

Third-party financing is funding for the SOE that does not come from its own resources (e.g. retained earnings) or from its shareholders (e.g. the government). It is financing from a third source (e.g. a private company, or bank), either through debt or equity.

- Debt: Debt is an amount of money borrowed by the SOE from another entity. It can be through bank loans, lines of credit, the issuance of bonds or Eurobonds. Debt has a maturity (length of time) and an interest rate (or coupon in the case of bonds). The question is whether the SOE has the statutory right to raise debt (e.g. bank loans or bonds).

- Equity: Equity is the SOE’s assets after liabilities have been deducted. It represents a share of ownership in the SOE, rather than a debt that is due to be repaid. Equity is typically issued to investors through shares. The question is whether the SOE has the statutory right to raise funding through equity (e.g. by issuing shares to outside investors).

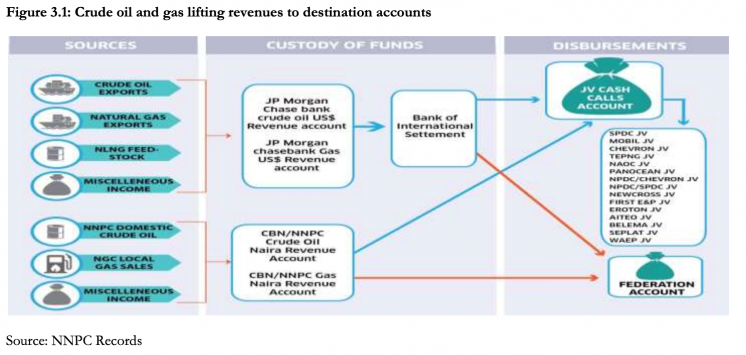

Nigeria: The management of state oil and gas revenues

Below, a diagram showing the flow of oil and gas revenues (including the proceeds from the state’s in-kind revenue) by NNPC (Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation).

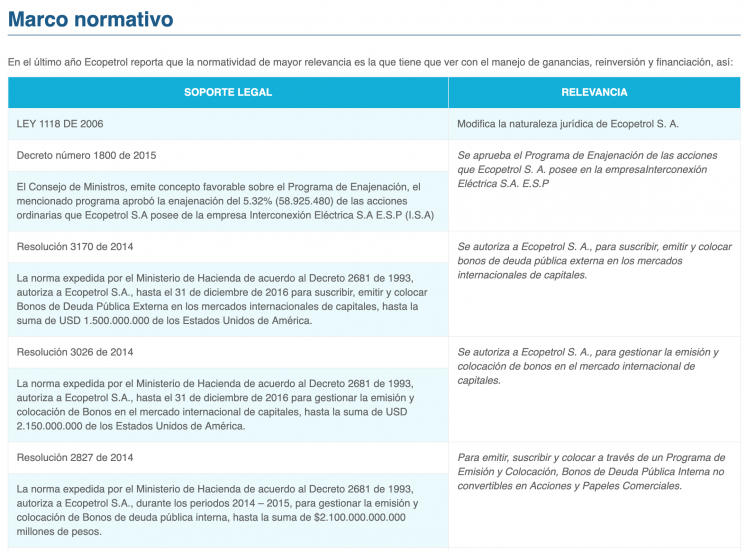

Colombia: Regulatory framework for SOEs

The 2017 EITI Report describes the regulatory framework for national oil company Ecopetrol’s financial relations with government.

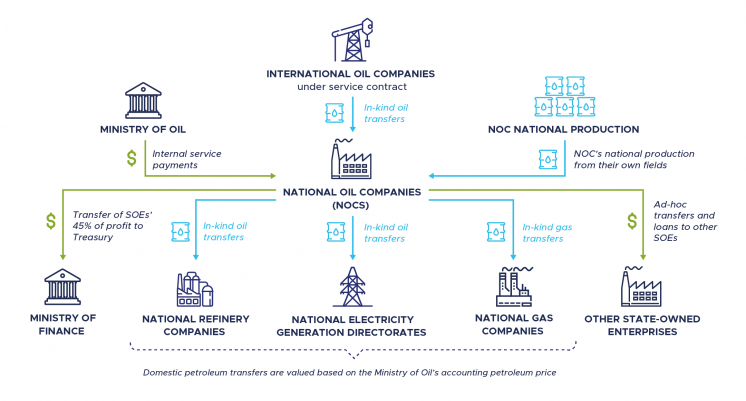

Iraq: National oil companies

While national oil companies in Iraq make only one type of payment to government (45% of NOCs’ net profits are usually not significant), the SOEs are considered material in terms of exploration, production and receiving material transfers (Internal Service Payments).

Step 6: Describe the financial relations between SOEs and government in practice

Relevant government entities and SOEs should disclose information on the prevailing practices regarding the financial relationship between the government and SOEs, and between SOEs and SOE joint-ventures or subsidiaries. EITI reporting should provide an annual diagnostic of adherence to the statutory rules governing SOEs’ financial relations with the state (as described under Step 4) in practice. References to all publicly available information should be provided and address information gaps be addressed where necessary.

As a starting point, the MSG should review the monitoring and oversight arrangements of each SOE, including their annual reports, financial statements, sustainability (ESG) reports, stock exchange filings (if applicable), etc. The following rough equivalents can be helpful when reviewing SOEs’ financial statements:

- dividends: distribution of profits, statement of cash flows as a use of cash under the heading financing activities’, statement of stockholders' equity as a subtraction from retained earnings;

- budget transfers/subsidies: government grant, government assistance, other income – state;

- retained earnings: net earnings after dividends, surplus;

- reinvestment: investment on own account/self-financed;

- third-party financing including debt or equity: short-term loan, long-term loan, line of credit, bond, Eurobond, and equity, shareholding, share issue, etc.

For each SOE, the MSG could consider using a standard table to guide its data collection, drawing from the example of Kazakhstan below.

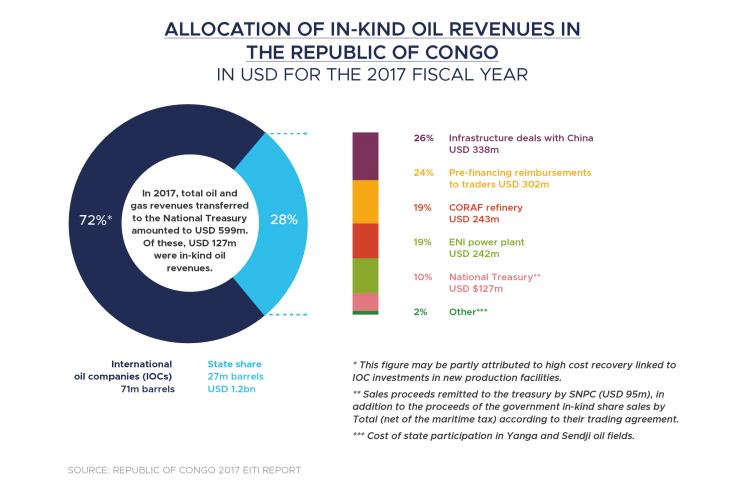

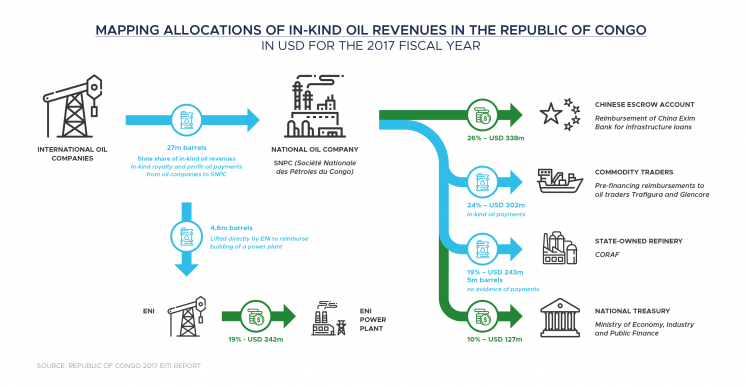

Republic of the Congo: Transactions involving an SOE

Below, transactions involving the national oil company SNPC (Société nationale des pétroles du Congo).

In recent years, SNPC has withheld a large share of the proceeds from the sale of the state’s in-kind revenues, to pay off infrastructure loans and crude barrels for the national refinery off-budget.

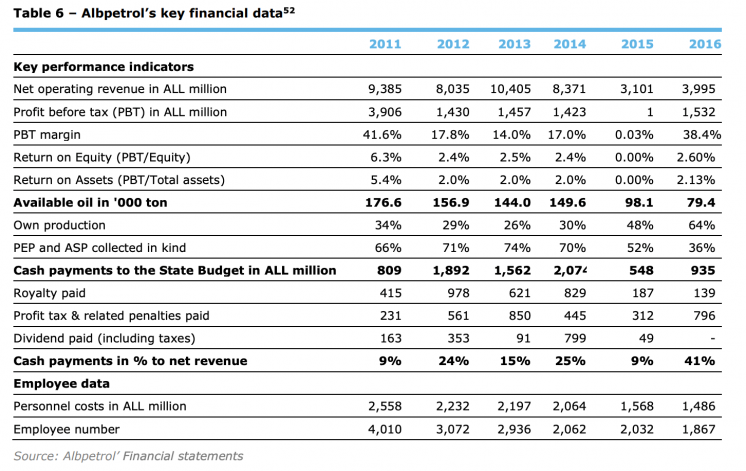

Albania: Audited financial statements

Below, excerpts from national oil company Albpetrol’s 2011-2016 audited financial statements.

These show the use of Albpetrol’s retained earnings.

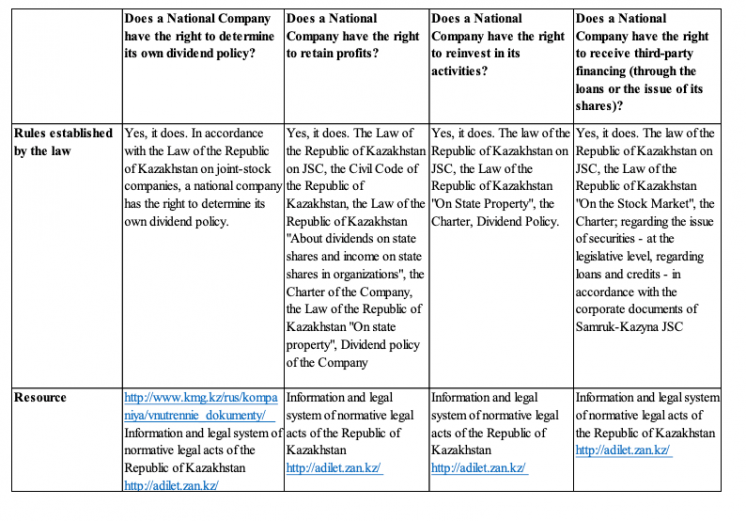

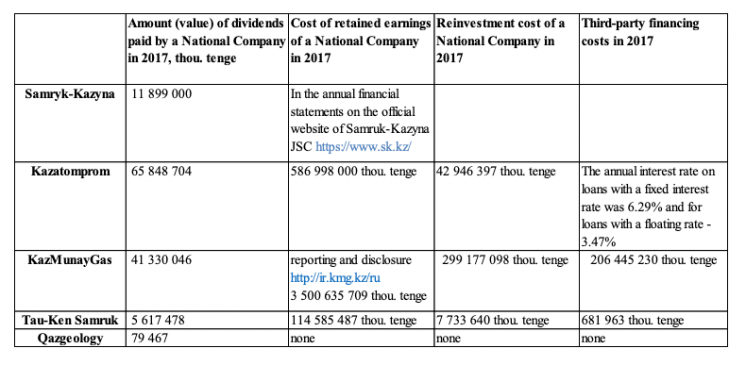

Kazakhstan: Data collection

Below, an example of a data collection table showing a diagnostic of the rules and practices related to SOEs’ financial relations with the state.

Step 7: Describe any state or SOE loans or loan guarantees to extractives companies

The MSG should identify any active loans or loan guarantees from the state or from any SOE to any extractives companies or projects. Disclosures should include the loan or guarantee’s tenor (i.e. the length of time until it is due) and key terms such as the repayment schedule and modalities, and interest rate. The MSG is encouraged to also consider any SOE loans and guarantees to non-extractives companies and projects.

Transparency in the provision of loans and guarantees from the state and SOEs to extractives companies is key to understanding the level of state financial support for mining, oil and gas companies, usually using taxpayer funds. Governance risks include subsidising private commercial companies, patronage through preferential lending to politically-exposed persons and off-budget loans by SOEs that are not reflected in sovereign debt statistics. In analysing disclosures, the MSG might also wish to compare the terms of these loans and guarantees to commercial loans, as encouraged by the EITI Standard.

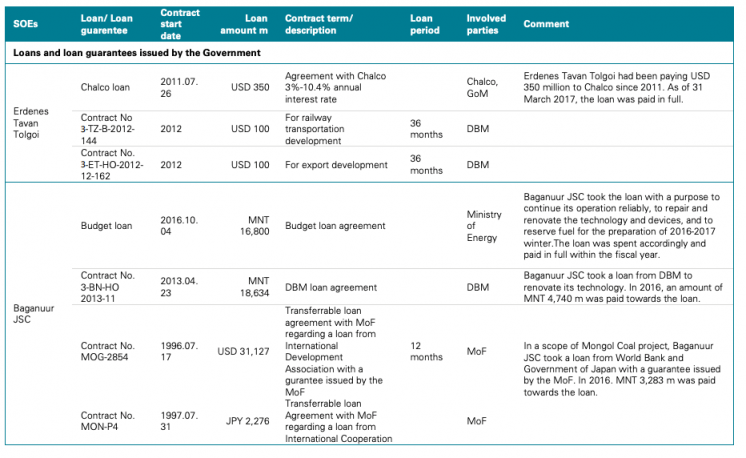

Mongolia: Loans and guarantees

Below, an example of the complex list of loans and guarantees involving mining SOEs from Mongolia’s 2017 EITI Report, although missing the terms of the loans.

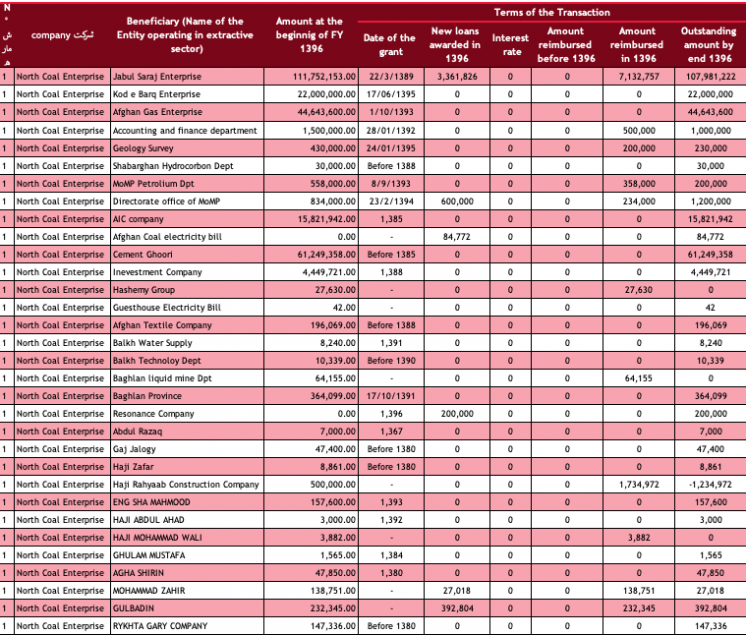

Afghanistan: SOE loans at preferential terms

Below, a list of extensive interest-free loans by North Coal Enterprise, including to extractives companies.

Step 8: Liaise with each material SOEs on the publication of their financial statements

Material SOEs are expected to ensure that their audited financial statements are publicly accessible. The latter should include not only the auditor’s opinion and a summary of key financials, but also the company’s full set of audited accounts, including its profit and loss statement, balance sheet and cash flows. Explanatory notes detailing the definition of key terms and accounting practices should be included.

The MSG should liaise with SOEs to assess the public accessibility of their financial statements. For SOEs that do not routinely publish their financial statements, the MSG should work with SOEs to identify any objections to such publication and find intermediary solutions. In cases where SOEs may not have financial statements, the MSG should liaise with SOEs’ management to ensure that the main financial items are publicly disclosed, including their balance sheet, profit and loss statement and cash flows. The MSG should also consider whether the SOE and relevant government entities providing information related to state participation are subject to credible, independent audit, applying international auditing standards, in accordance with Requirement 4.9 of the Standard. The MSG should assess whether financial statements were prepared based on international accounting standards and whether they were audited in line with international standards.

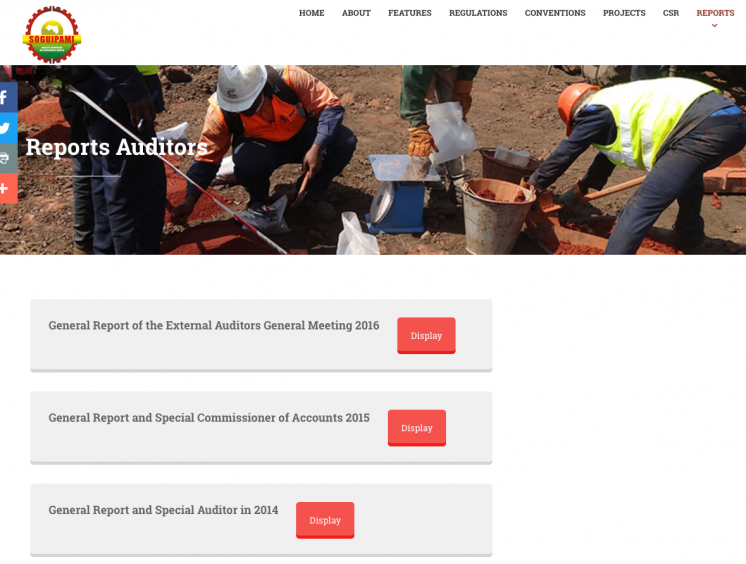

Guinea: Audited financial statements

The national mining company SOGUIPAMI (Société Guinéenne du Patrimoine Minier) publishes its audited financial statements annually.

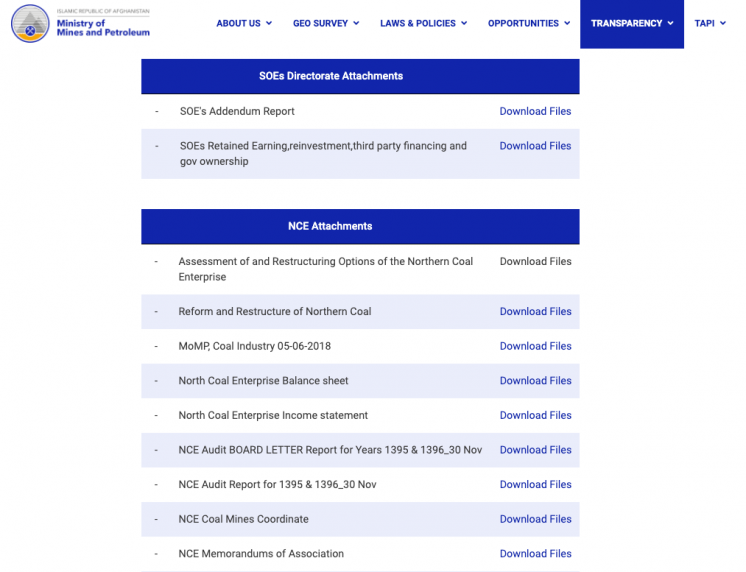

Afghanistan: Summaries of financial statements

Afghanistan systematically discloses the rules related to SOEs’ financial relations with the state. The government publishes the audited financial statements of its two SOEs on its website, showing how these rules are carried out in practice.

Step 9: Explore disclosure opportunities for SOEs’ procurement, subcontracting and corporate governance

The MSG is encouraged to consider opportunities for disclosing additional information on SOEs’ management of expenditures (operating and capital), procurement, subcontracting and corporate governance. The latter can include disclosures around the composition of the Board of Directors, appointment of the Board of Directors and management, the mandate of the Board of Directors, and any code of conduct that would apply to SOEs’ management staff. The MSG could also consider conflict of interest policies for the Board of Directors and management.

An analysis of existing data through EITI reporting would help shed light on governance risks, such as the use of operating expenditures to cover non-core spending, procurement secured by SOEs at different rates than commercial ones from companies owned by politically-exposed persons, political interference in the appointment of SOEs’ Board of Directors and the absence of safeguards against conflicts of interest in the management of SOEs’. Such an analysis could also contribute to an audit of an SOE’s functioning in accordance with its mandate.

The MSG could consider the following aspects in its review of SOE expendituresHideSee for instance PIAC (2018), Annual report on the management and use of petroleum revenues for the period 2018.:

- Disaggregation by upstream, midstream and downstream;

- Expenditures on exploration, appraisal, development and production;

- Expenditures on infrastructure linked to processing, refining, transportation and distribution;

- Expenditures on core and non-core activities.

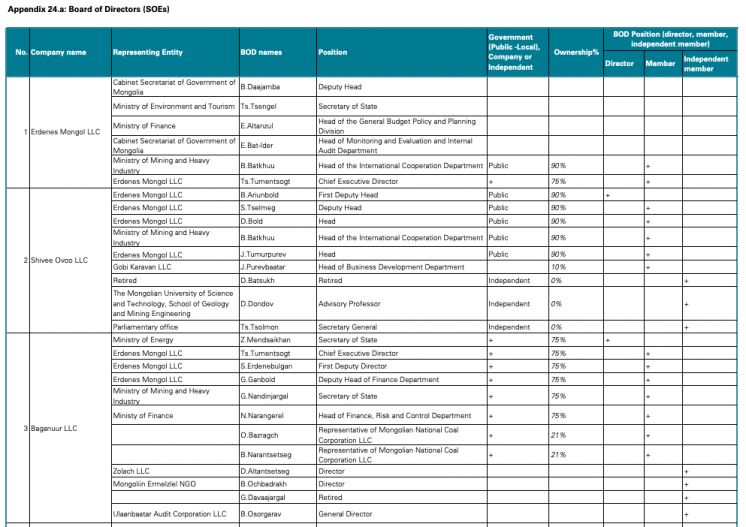

Mongolia: SOE Board of Directors

Below, an overview of the composition of the Board of Directors of SOEs in Monngolia.

Cameroon: Corporate governance

Below, a brief overview of the corporate governance of Cameroon’s national oil company SNH (Société Nationale des Hydrocarbures), with link to its organigramme.

Dissemination and use of data

Depending on the objectives defined in the EITI work plan, relevance in country and stakeholder demand, there may be various opportunities for MSGs to disseminate information on state participation and support stakeholders in using and analysing the data. Stakeholders in government may be interested in assessing whether revenues from SOEs are in line with the company’s performance and use the data as evidence on which to base key reforms, either towards socio-economic or corporatisation targets. Public oversight actors can analyse the disclosures to better understand the management of large shares of extractive revenues and assets on behalf of citizens.

Thematic reporting on SOE transparency in the DRC. Issues surrounding state participation in the DRC’s extractive industries have generated substantial public debate, most notably on largest mining SOE GÉCAMINES management of extractive licenses. Other SOEs have also attracted public attention over their perceived lack of transparency in management of government revenues following reports and analysis by civil societyHideTCC (2017), A State Affair: Privatising Congo’s Copper Sector, https://www.cartercenter.org/news/pr/drc-110317.html; Global Witness (2017), Regime cash machine: How the Democratic Republic of Congo’s booming mining exports are failing to benefit its people, https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/democratic-republic-congo/regime-cash-machine/.. The findings and recommendations from these studies were discussed by the MSG, which agreed to investigate the findings and improve SOE disclosures through EITI reporting. DRC EITI access were provided access to the 2016 financial statements of nine extractives SOEs for the first time, which were analysed by external consultants.

The analysis published by DRC EITI found that most of the financial statements were unaudited and there were inconsistencies in the types of documents SOEs provided. The analysis of financial statements also showed that i) SOEs did not consistently transfer shares of extractive revenues to the state Treasury as per the regulatory framework, ii) the main SOE did not adhere to existing rules with regards to the sale of state assets in its joint-venture operations, iii) SOEs were operating despite losses year after year, and iii) GÉCAMINES had contracted commercial loans from private companies, including commodity trader Trafigura and largest mining project in the DRC Tenke Fungurume. As of April 2020, the MSG was preparing a follow-up report on state participation to further clarify disclosures under Requirement 2.6.

Further resources

- EITI (2018), Upstream Oil, Gas and Mining SOE Governance Challenges

- World Bank (2014), Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises: A Toolkit

- OECD (2017), Preventing Corruption and Promoting Integrity in State-Owned Enterprises: Highlights

- NRGI (2015), State Participation and State-Owned Enterprises: Roles, Benefits and Challenges

- NRGI (2018), Guide to Extractive Sector State-Owned Enterprise Disclosures

- IMF (2007), Fiscal Transparency Manual 2007

- IMF (2019), Fiscal Transparency Initiative: Integration of Natural Resource Management Issues