Defining and capturing data on the ownership and control of state-owned enterprises

This guidance note has been produced for the Opening Extractives programme which is jointly implemented by the EITI and Open Ownership.

Overview

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) are a critical part of the global economy and play a prominent role in natural resource governance in many countries.

Transparency about how SOEs are owned or controlled is crucial to understanding if they are being run for the benefit of the public. It helps to identify corruption and reputational risks and to meet the broader aims of beneficial ownership reforms.

This guidance explores what information is needed on the corporate governance of SOEs to support transparency efforts. It demonstrates how capturing high-quality structured data on SOE ownership or control structures aids information-checking, as well as helping satisfy Requirement 2.6 of the EITI Standard.

This guidance has been produced as part of the Opening Extractives programme which is implemented jointly by the EITI and Open Ownership. Opening Extractives aims to transform the availability and use of beneficial ownership data for effective governance in the extractive sector.

Summary

This guidance note supports implementers of beneficial ownership registers. It focuses on why more transparency is needed about the corporate governance of SOEs, sharing considerations on defining and declaring their ownership or control.

While SOEs play a critical role in the global economy, opaque ownership and control of SOEs risk creating a weakness which could undermine the specific aims of beneficial ownership transparency reforms.

The specific risks associated with SOEs and their prominent role in natural resource governance in many countries make it crucial for there to be a greater understanding of information about SOEs above and beyond standard beneficial ownership practices, which often focus on ownership through shareholding.

There are five main considerations for government implementers captured within this guidance:

- Defining SOEs

- Ensuring comprehensive coverage of SOEs

- Establishing which control mechanisms to record

- Deciding whether to list individuals or role titles

- Capturing structured data

Case studies in this document are primarily drawn from the collation of publicly available information on two SOEs and the representation of this information as structured data.

The case studies chosen are Pertamina, a state-owned oil and natural gas corporation in the Republic of Indonesia, and the Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC), a for-profit oil corporation that partners with foreign companies to extract Nigeria’s fossil fuel reserves.

Learnings from this exercise helped to establish key areas for consideration by governments seeking to adopt a more structured and standardised approach to collecting information on the ownership and control of SOEs as part of a disclosure regime.

Key concepts

SOEs play a critical part the global economy and have a unique potential to drive economic growth. SOEs in the extractive sector play an important role the production and sale of natural resources and may, thereby, generate significant revenue for the state. International bodies, including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), stress that SOEs “should observe high standards of transparency” relating to information about how they are managed.

Not having visibility of how SOEs are owned and controlled would constitute a considerable weakness that could undermine the specific aims of beneficial ownership transparency reforms. Beneficial ownership registers are a logical solution for identifying and monitoring state ownership of companies.

The specific risks of opaque ownership and control of SOEs include: a lack of visibility of the transfer of assets between private and public sectors; the misuse of SOE resources; not understanding the impact of SOEs on the economy; and not understanding the impact of any cross-border activity undertaken by SOEs.

These specific risks are addressed in Open Ownership’s definition of beneficial ownership:

Beneficial ownership is a natural person’s right to some share or enjoyment of a [legal entity’s] income or assets (ownership) or the right to direct or influence [the entity’s] activities (control). Ownership and control can be exerted either directly or indirectly

From this definition, it follows that the purpose of beneficial ownership disclosures is to establish which individuals are the beneficial owners of entities, where beneficial ownership can be exercised through ownership and/or control. States or state bodies, such as government ministries or agencies, often hold direct or indirect controlling interests in SOEs, in addition to ownership stakes like shareholdings. Beneficial ownership transparency requires an understanding of who the individuals are who exercise these controlling interests on behalf of the state. Because of this, it is recommended that government implementers place a strong emphasis on understanding how SOEs are controlled.

Of 347 SOE respondents, 42% reported that corrupt acts or other irregular practices transpired in their company during the last three years, according to a 2018 OECD survey.

Considerations

1. Defining state-owned enterprises

The OECD defines an SOE as being “under the control of the state, either by the state being the ultimate beneficial owner of the majority of voting shares or otherwise exercising an equivalent degree of control.

The EITI defines an SOE as a wholly or majority (50%+1 share) government-owned company that is engaged in extractive activities on behalf of the government.

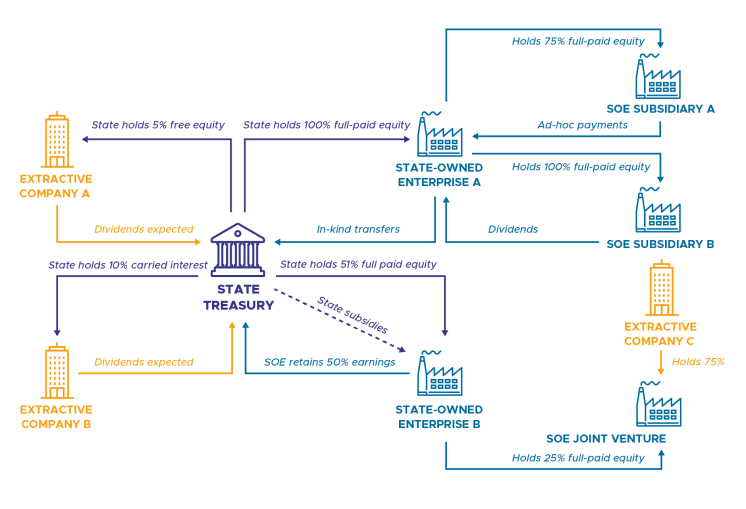

SOEs often have complex corporate structures – sometimes spread across multiple jurisdictions – which intertwine with governments in diverse ways via direct or indirect ownership stakes or controlling interests.

A state can be a minority owner and still exercise significant influence and control over a company or an SOE.

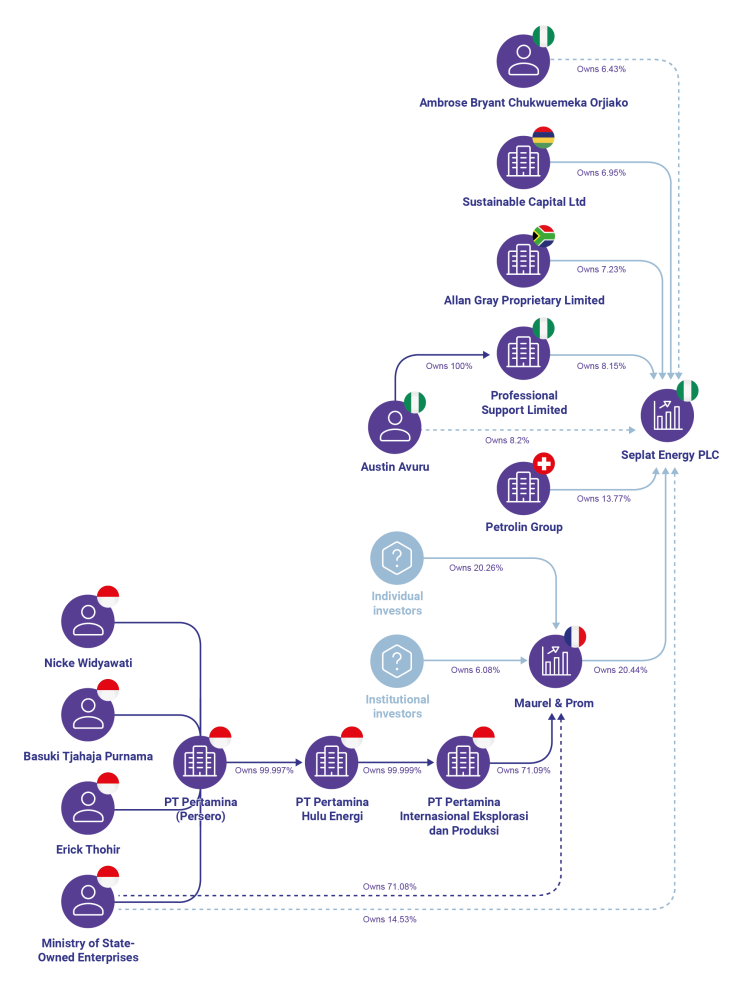

The diagram above shows the Indonesian SOE Pertamina and one arm of its subsidiaries and associates. Pertamina owns a majority shareholding of 71.09% in Maurel & Prom. It, in turn, is the largest single shareholder in the publicly listed Nigerian oil and gas company Seplat Energy PLC, with a 20.44% stake.

This example illustrates some of the considerations that would need to be taken into account by various parties in their beneficial ownership regimes, for instance:

- The Nigerian government may wish to ensure that foreign state interests, such as that of Pertamina, fall within their beneficial ownership disclosure regime.

- The French government may wish to ensure that Pertamina’s ownership interest is declared by Maurel & Prom.

In Indonesia, to be considered an SOE, at least 51% of shares must be directly owned by the state. By setting a definition with a threshold as high as 51% and requiring direct government ownership, Indonesia’s list of SOEs will exclude companies, such as Maurel & Prom, where the government has substantial ownership or control stakes, albeit indirectly or just below a majority. This makes it more difficult to get a holistic picture of state ownership globally, hindering transparency and anti-corruption initiatives.

By over-relying on ownership mechanisms, such as shares, there is a risk of excluding SOEs that are controlled by the state in other ways. It is common for legislation to set out additional rights, such as appointing both executive and non-executive positions, and companies themselves may have clauses in their articles affecting control.

With reference to Maurel & Prom, shares held for more than four years, without interruption, confer a double voting right. While this clause is not exclusive to SOEs, it highlights the complexity of control mechanisms. Clauses like this can result in changes in beneficial ownership without changes in shareholdings, and where such shares are held by government, such rights could potentially result in a company falling under the definition of an SOE.

When defining an SOE, consideration should be given to the following:

- Shareholdings and thresholds

- Direct and indirect ownership and control

- Foreign entities, states and interests

2. Ensuring comprehensive coverage of state-owned enterprises

It is important to ensure that any beneficial ownership regime will comprehensively cover SOEs in complex organisation chains, taking into consideration the fact that SOEs can take many forms and be set up through different mechanisms, such as by statute. Without robust legislation, these mechanisms may exclude them from the scope of the disclosure regime.

In Nigeria, businesses are regulated by the Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC). The CAC register shows the control of NNPC by two government ministries – the Ministry of Petroleum and the Ministry of Finance, both of which contain special divisions that are incorporated by statute. As instruments of government ministries, no further information about their involvement is held on the CAC register. This makes it difficult to gather a detailed picture of control.

To comprehensively cover SOEs, consideration should be given to the following:

- Scope of the legislation

- Legal forms

- SOEs created by statute

3. Establishing which control mechanisms to record

The importance of control

Unlike in the case of an ordinary business, for SOEs, the people whom the state represents have no direct relationship to the entity – neither in regard to the usual benefit of profit, nor in control over operations. However, SOEs deploy public funds. It is therefore taxpayer money that has been invested and is at risk, as well as, potentially, the state’s natural resources, reinforcing the need for transparency to enable accountability and oversight.

In any declaration by an SOE, it is recommended to capture information about the state or state agency involved – this is in addition to the usual information required about natural persons, to be able to comprehensively understand their ownership and control. In this context, only declaring the state ownership of an SOE is insufficient, and more focus should be put on those in control and the benefits that may arise from their positions of stewardship.

Benefits are not limited to remuneration and also include operational activities, such as a preferred status or advantage within a particular market; the choice of trade and procurement partners; and the ability to conclude other contracts. Successfully stewarding an SOE may also bring a level of prestige to an individual, granting them further personal opportunities.

Exploring control mechanisms

The ways in which states exert ownership or control over SOEs can be complex and often fall outside established definitions of beneficial ownership, requiring specific regulations and guidance to give clarity on the types of interest that should be disclosed. In the absence of the usual types of individuals who meet the criteria of beneficial ownership, it is not uncommon for legislation to specify othersHideE.g. “...there shall be entered… as its beneficial owners… the names of the one or more natural persons who hold the position of senior managing officials of the relevant entity” S.I. No. 110/2019 - European Union (Anti-Money Laundering: Beneficial Ownership Of Corporate Entities) Regulations 2019, Article 5, paragraph 4. who have a degree of control over the business and/or details on persons holding particular positions in a company.

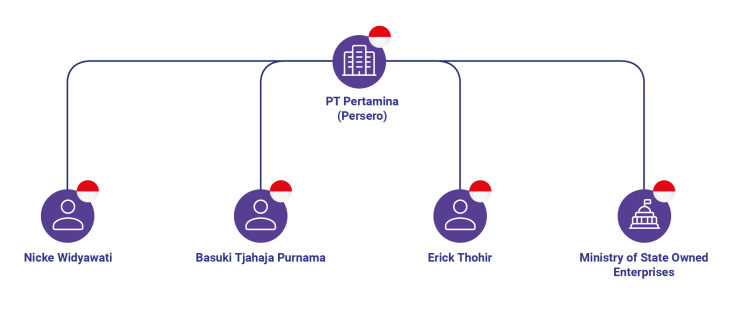

Although not often identified explicitly in legislation, and sometimes explicitly excluded from qualifying as beneficial owners in the case of ordinary companies, senior managing officials (SMOs) are the most relevant individuals in SOEs, alongside government officials. SMOs are the individuals exercising control over the organisation, and their powers or appointment are usually mandated by law. Deciding which SMOs to include in beneficial ownership declarations will depend on policy aims and local organisational structures, but it is recommended to include executive-level managers as well as board-level positions.

Public information on SMOs in Pertamina’s case shows the positions of the CEO, the Board President (also the CEO in this instance) and the President Commissioner. A more comprehensive approach would be to also list all members of the executive board and oversight commission.

Mapping the senior officials and government ministry which exert control over Pertamina

As information about the control of SOEs can be found in a range of legislative instruments, a comprehensive review of relevant legislation should be undertaken to identify SMOs. The source of this information will vary across jurisdictions. For example, NNPC is required by recent specific legislation on the petroleum industry in Nigeria to have two ministers on its board during the period that it is wholly government-owned. Previously, this type of detail was found in the statute that created NNPC. In Indonesia and in the case of Pertamina, the legislation specifies that it is the responsibility of a particular minister to appoint the SMOs alongside other oversight powers which are granted through legislation on the remit of the Ministry of State Owned Enterprises.

When establishing which control mechanisms to record, consideration should be given to the following:

- Board members and their appointment process

- Senior managing officials

- Role of government officials

- Control by legal framework

- Other influence and control

These types of control can all be captured within the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (BODS), an open standard developed and managed by Open Ownership and Open Data Services.

4. Deciding whether to list individuals or role titles

Due to their structure and mandate, the ownership or control of SOEs frequently involves politically exposed persons (PEPs). The Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the international anti-money laundering standard setter, defines a PEP as “an individual who is or has been entrusted with a prominent function”, adding that “many PEPs hold positions that can be abused for the purpose of laundering illicit funds or other predicate offences such as corruption or bribery”. PEPs often play roles that enable them to exert influence in ways which may not be immediately obvious or declarable under a country’s definition of beneficial ownership.

In some jurisdictions, such as the examples above, legislation confers influential roles on ministers or leading politicians due to their political position.

There are several reasons why public information on SOEs should list ministers and leading politicians as individuals rather than as their positions:

- A key principle behind beneficial ownership is that there is a natural person at the end of the control chain. Declaration of a position does not identify the individuals who hold or have held that position.

- Different individual ministers may have a range of declarable ownership interests beyond those bestowed upon them by their position, and these may be relevant for accountability and identifying potential conflicts of interest.

- Because individuals move between political positions, recording individuals rather than their roles makes it easier to form a picture of timelines of control.

- It is simpler to link individual data on the control of SOEs with other data on a beneficial ownership register.

- The data is easier to use and interpret, as it does not rely on assumptions of prior knowledge on the part of the user.

Implementers should consider the benefits of identifying individuals as opposed to their roles, as this strengthens the quality of beneficial ownership data and assists transparency.

5. Capturing structured data

The Pertamina example used throughout this document, and seen in full in the diagram below, shows how complex SOEs can be. The information above follows only one track of a subsidiary out of over 100 direct and indirect subsidiaries and associates spanning the globe.

The Pertamina example used throughout this document, and seen in full in the diagram above, shows how complex SOEs can be. The information above follows only one track of a subsidiary out of over 100 direct and indirect subsidiaries and associates spanning the globe.

Substantial time was needed to compile this limited data from public sources, including websites, reports and government registers. The collection and publication of this information in structured data formats, such as BODS, would make these types of tasks more accessible.

Publishing this information as structured data would also better support and allow for the kind of analysis and visualisation carried out above. Keeping this information more up to date and auditable so as to “identify any changes in state ownership of interests in extractive companies” within a given year will make records easier to check; satisfy international standards for timeliness; and help satisfy Requirement 2.6 of the EITI Standard.

Based on EITI assessment criteria, Open Ownership recommendations and research conducted to explore the examples used in this guidance, governments should consider capturing detailed information on all of the following to fully understand the ownership or control of SOEs:

- The SOE

- The state’s role or interests in the SOE

- The state body or bodies which own or control the SOE, or the state itself where the details of the state body are not available

- Beneficial owners of the SOE

- Joint ventures

- Information gaps in disclosures

These echo and reinforce related recommendations from the OECD, the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) and a coalition of transparency advocacy groups. Full field details for these areas can be found in Appendix A.

For ease of collection and use, consideration should be given to collecting, storing and publishing this information in a structured data format, such as BODS.

Conclusion

SOEs form an important and growing part of the global economy, with networks that span many contexts. Transparency about how they are owned or controlled is crucial to understanding if they are being run for the benefit of the public; to identify corruption or reputational risks; and to meet the broader aims of beneficial ownership transparency reforms. It can be challenging to gain a full understanding of how SOEs are owned or controlled due to the complexity of their networks and connections, as well as their less common mechanisms of control. Governments and citizens can benefit from strengthening legislation relating to definitions and thresholds for ownership or control disclosures and require SOEs to publish timely, comprehensive and structured data, following the steps outlined in this guidance.