Overview

This technical guidance is part of a series on emerging topics related to the effective implementation of beneficial ownership transparency reforms. It is aimed at technical professionals, especially those with a role in the technology architecture of registers that publish beneficial ownership data. The thinking set out here will inform future updates to the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard.

This guidance has been produced as part of the Opening Extractives programme which is implemented jointly by the EITI and Open Ownership. Opening Extractives aims to transform the availability and use of beneficial ownership data for effective governance in the extractive sector.

Keeping up to date and historic beneficial ownership records underpins any transparency initiative around company ownership and control, and is one of the Open Ownership Principles for Effective Beneficial Ownership Disclosure. It is for this reason that many business registers now require the timely reporting of changes to beneficial ownership. But just as crucial is ensuring those records are easy to access, interpret and check; that is, that they are auditable.

Introduction

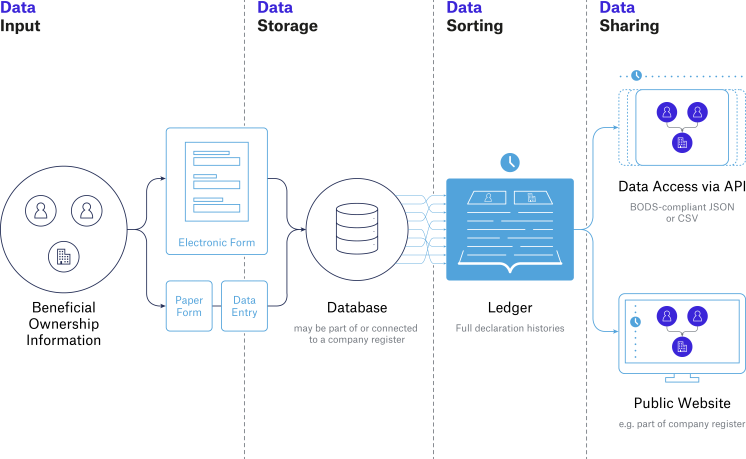

A record of beneficial ownership can be seen as a ledger of information that builds up over time. New information about the ownership and control of an entity supersedes older information as shares are sold, company rules are updated, and new companies are incorporated. This forms part of a well-designed beneficial ownership declaration and storage system. It can then be shared as necessary.

As with an accounting ledger, beneficial ownership information needs to be recorded and organised in a way that makes accessing and understanding it as easy as possible. The kind of questions people ask about beneficial ownership point to the features which are required of the ledger.

Example questions/searches:

- What did the beneficial ownership of the company look like in September 2021?

- What other companies did a particular beneficial owner act as a director of at that time?

- How did that beneficial owner's disclosed interests in the company change during the course of 2021? Were those changes reported within the legally-required timeframe?

- What reason was given for no beneficial owners at all being disclosed a year earlier?

To answer these questions we need companies and individuals to be identifiable, the source of information to be traceable, all information to be reliably dated, and gaps in expected information to be both visible and explained. Alongside these features, the more structured, standardised and machine-readable the data is, the easier it becomes to search, sort or explore, as is explained in this structured data briefing.

Features

1. Reliable and comprehensive dates and times

What did the beneficial ownership of the company look like in September 2021?

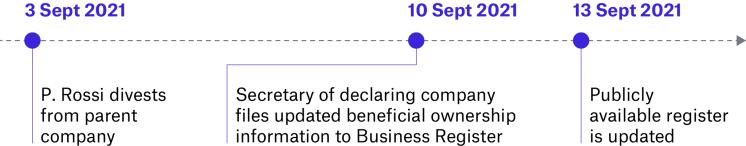

Answering a question like this means picking through historic information. It also requires a good understanding of how reported information reflects a timeline of real world events.

Broadly, dates and times in beneficial ownership ledgers tell us:

- When a feature of beneficial ownership existed

- When details of that feature were reported

- When the information was added to the ledger

For example, a person might divest from a company on a certain date and cease to be a beneficial owner. That information might be reported seven days later, but only be visible via a business register website ten days later.

Publishing such dates as part of a ledger allows us to recreate timelines and to picture a company’s ownership and control at a particular point in time. When dates are published, therefore, it is important to be clear about what they mean. For example, consider a person's name alongside a date titled 'Beneficial ownership date'. It is not immediately clear whether that is the date on which their relevant interests in an entity started, ceased, or the date on which they were reported. A well-maintained publication policy or data-use guide can be a great help when it comes to interpreting information accurately (see the final feature below).

A good starting point when considering the kinds of dates that will need to be recorded by a declaration system are the reporting regulations of the country concerned. These should specify the particular events that trigger beneficial ownership information to be disclosed, updated or confirmed. For example, initial registration of an entity, a change of beneficial owner or annual reporting requirements might all trigger a declaration to be made. There are likely to be related sanctions for non-compliant reporting, so collecting accurate date information is critical for flagging non-compliance. This is covered in more detail in the paper ‘Designing sanctions and their enforcement’.

On a practical note, some dates might be captured within a declaration form (for example, ‘Date that individual ceased to be a beneficial owner’) whereas others might be metadata collected automatically by an online system (for example, ‘Date of declaration submission’).

The Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (BODS) supports the publishing of crucial dates relating to beneficial ownership declarations. Open Ownership will also be developing guidance on how to understand and use date fields across the data schema. All of this means that producing a point-in-time snapshot of a company’s ownership and control becomes a reliable and reproducible process.

- Registers should capture crucial dates for changes and should format these in line with internationally recognised standards such as ISO 8601.

2. Reliable identifiers for people and entities

What other companies did a particular beneficial owner act as a director of at that time?

This question is very difficult to answer if individuals are not identified in a common and unambiguous way within declarations from all companies. A name is not enough to guarantee that a person or entity can be correctly identified. A unique reference such as an ID card number, an internal database key, or a company registration number (along with information about the issuing authority) can help identify the individual or entity in the real world.

These identifiers have a further function: they allow information about an individual or an entity to be brought together when it is disclosed at different points in time, or by different agents. Of course, considerations of data protection and privacy require that minimal personal information about individuals is made public, while still ensuring that the data is usable. This might mean that minimal descriptive fields relating to an individual are published; for example, just a name and a birth month and year. However, non-identifying internal references or identifiers can also be published so that an individual’s connections with multiple entities is made transparent.

BODS allows different types of identifiers to be published for people (and for entities). So, for example, a non-identifying internal reference number FFT-826-HKE908 could be published for a particular beneficial owner. Finding out what other companies they are a director of would then simply involve searching records of directors for the same “FFT-826-HKE908” reference.

- Good-quality unique identifiers should be provided for people and entities so that changes in beneficial ownership can be connected to the correct records.

3. Traceable source information

How did a beneficial owner's disclosed interests in a company change during the course of 2021? Were those changes reported within the legally-required timeframe?

Declaration source

When it comes to investigating the beneficial ownership of particular entities, or designing red-flagging systems, it is critical to find out who knew what, and when. The ‘when’, has been covered with feature two above. The ‘who’ is just as important: analysts need to know the company or individual that declared the information was accurate.

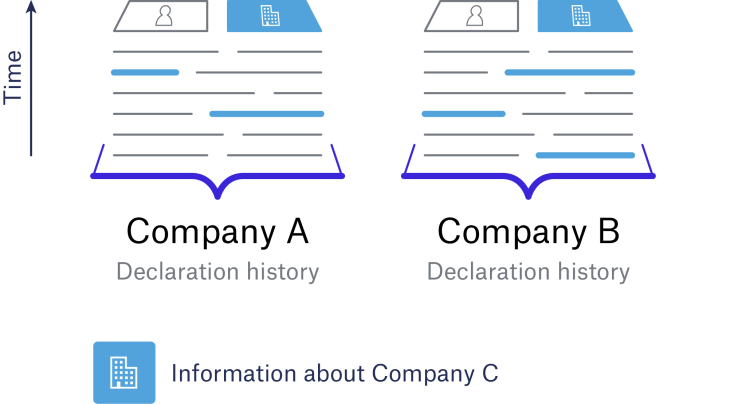

Companies, individuals and agents may appear in the declaration ledgers of different companies and at different points in time. Analysts need to be able to compare what was disclosed in one place at a given time with what was disclosed elsewhere. Imagine, for instance, that Company C is disclosed as an intermediary for a beneficial owner in declarations from both Company A and Company B.

It is known that Company C’s name and ownership changed over a six-month period, and therefore this impacted the beneficial ownership of Company A and Company B. In an investigation, it could be crucial to know when these changes were disclosed, and which of the related companies disclosed them.

For this reason, BODS represents a declaration about beneficial ownership as a collection of statements about entities, people and their relationships. This allows analysts to consider and compare statements about the same entity (or individual or relationship) which were made at different points in time, by different sources.

Understanding the motivation for updates

To make sense of competing statements about the same individual or entity, it helps to know what has triggered an information update. Of course, the existence of a new beneficial owner or similar changes to a real world situation might trigger updated information to be disclosed, then added to the ledger. However there are other types of motivations for updating information which include:

- The disclosed information was wrong and has been corrected by the declaring person;

- The disclosed information was incorrectly represented by the system and has been corrected;

- The disclosed information should not have been published.

Only the first of these examples describes a mistake by the declaring person at the point of data input. The other two cases describe mistakes at the data storage and publication stages.

Consider the above examples and the huge range of reasons that an element of beneficial ownership information might change. It becomes apparent that not all updates should be part of the ledger, and some updates may exist to correct the historical record.

We would expect in case (1) that the inaccurate information would remain part of the historical record, and the update (and the motivation for it) would be part of the ledger. In case (2), the error came from the system’s data handling. Here it would be acceptable to correct the historic record transparently (publishing the motivation for the correction), so that if the erroneous and corrected data are compared, it is clear which is which.

Case (3) is different. Here information has been published to the ledger which should have been kept private. Historic records in the ledger need to be redacted in a way that does not draw attention to the redaction: the motivation for the update need not be made apparent.

Of course, declaration systems should be designed so that the motivation for updates is also recorded internally. But, as we have seen, not all changes should be made to the published beneficial ownership ledger in the same way.

These considerations are all informing how we improve BODS. The data schema and the guidance will provide a strong steer as to how ledgers of beneficial ownership look when produced as JSON data conformant with BODS. Questions like “Were […] changes reported within the legally-required timeframe?” can then be translated into queries over historical datasets.

- When changes are made to beneficial ownership records, data should be captured about who is updating the information and what type of change is being made.

4. Visible information gaps

"What reason was given for no beneficial owners at all being disclosed a year earlier?"

When examining a ledger of beneficial ownership, information that we expect to see may sometimes be missing. That might be for any number of reasons, for example:

- by design (for instance, because an entity is exempt from reporting its beneficial owners);

- failure by the declaring person to disclose information;

- failure of the declaration system to retrieve information;

- information being legitimately withheld from publication by the declaration system (for example, under the provisions of a protection regime).

Sometimes an information gap will itself form a feature of the ledger, for example, when an entity reports that it has no beneficial owners at a given point in time. Sometimes the information gap will only be visible and explained outside the ledger: for example, a company shows up in a public record of entities which are exempt from beneficial ownership reporting. But in most cases, the gap in the information should be made apparent within the ledger and its reason made clear.

BODS already goes some way to accounting for information gaps, but there is more to be done to address the full range of relevant information gaps. Whether using BODS or another standardised format for publishing beneficial ownership data, it should be a simple matter to determine which entities have disclosed no beneficial owners, and why.

- If information is missing from beneficial ownership records, registers should be able to capture the reasons why it is missing, rather than just leaving a gap.

5. Publication policy

Imagine being faced with stacks or gigabytes of beneficial ownership declarations - multiple ledgers in a big heap. Any additional resources that support people to make sense of the information are invaluable.

Open Ownership suggests that publishers consider providing a publication policy or data use guide alongside any beneficial ownership data. This provides an instruction manual for approaching the data, and a repository of useful, supporting information. Thinking about the features identified above which make for auditable ledgers, a publication policy might contain answers to questions like:

- How are companies which are exempt from reporting represented in the data?

- Why does a particular information field disappear from declarations after a certain date?

- How does a particular correction to a system error appear in the data?

- Where can definitions of the codes in the data be found?

- What identifiers are used for individuals and entities and can they be reliably used for de-duplication?

A publication policy which keeps pace with the way that beneficial ownership records are presented unlocks the full value of current and historic information.

- Publishers could release an instruction manual for any source of beneficial ownership data to help answer questions from data users.

Conclusion

The features identified above are far from exhaustive. Others - like producing information as structured, machine-readable data rather than in PDF - are just as important for making records of beneficial ownership usable. The important thing is to consider what questions people want to ask of the historical record, and how they will go about their enquiries. By considering the foundational reasons for beneficial ownership transparency, designers and system architects have the best chance of building the systems that analysts and investigators need now, and for the future